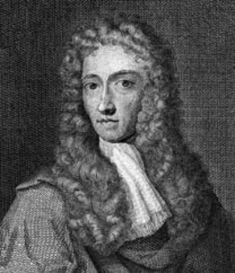

| Robert Boyle | |

|---|---|

|

|

| First Modern Chemist | |

| Specialty | Physics, Chemistry |

| Born | Jan. 25, 1627 Lismore, County Waterford, Ireland |

| Died | Dec. 31, 1691 (at age 64) London, England |

Robert Boyle was an Anglo-Irish scientist and inventor. He is generally considered to be the first distinguishable modern chemist and an innovator in the development of scientific experimentation. His most significant discovery was Boyle’s Law, which connects a gas’s volume and pressure. Boyle’s pioneering work in chemistry was underpinned by his 1661 book, The Sceptical Chymist. Especially in his younger days, he was also a considerable philosopher and theologian.

Boyle’s Early Life

Boyle was born at Lismore Castle in Ireland’s County Cork on January 25, 1677. He was the son of the Earl of Cork, one of the country’s most important men, and Boyle was to benefit from his high-born status throughout his life. When he was eight years old, he was sent to England to receive a formal education at Eton.

A few years later, he moved to Switzerland to receive private tutoring in Geneva. In 1644, his father died and Boyle went back to England, eventually setting up home at Stalbridge in Dorset, where he had inherited land from his father.

Boyle returned to Ireland in 1652 to find his family’s lands damaged from the effects of years of civil war. Nevertheless, he managed to undertake some scientific study, in particular chemistry which was the science that increasingly caught his attention.

Two years later, he went to Oxford and joined a group of leading men of science of the day. Boyle was quickly accepted by them after demonstrating his remarkable brain. By 1657, he was collaborating with his then assistant, Robert Hooke, on the design of a better version of the newly invented vacuum pump.

Boyle’s Law

With the help of the improved pump, Boyle was able to conduct detailed experiments regarding the properties of air, publishing his findings in 1660. He remained fascinated with the subject all his life, and the quality of his work remained unsurpassed for many years. In particular, Boyle studied the importance of air to the survival of living creatures, sound propagation, and combustion, as well as measuring its elastic properties.

He used a barometer to demonstrate that its column of mercury was held up by air pressure, and pointed out that the volume of a specific amount of air was inversely proportional to its pressure; this became known as Boyle’s Law.

The Sceptical Chymist

In 1661, Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist. Although the book was rather disorganized and tilted toward the theoretical rather than the practical, it was important for its author’s belief that experimentation should form the base of all scientific study. In the book, he showed that the previously accepted theories of Aristotle, in which there were only a small number of basic elements, were wrong.

In 1661, Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist. Although the book was rather disorganized and tilted toward the theoretical rather than the practical, it was important for its author’s belief that experimentation should form the base of all scientific study. In the book, he showed that the previously accepted theories of Aristotle, in which there were only a small number of basic elements, were wrong.

Boyle was a believer in the philosophy of mechanics, which stated that matter and motion were the basic building blocks of science. What he termed “corpuscular philosophy” explained matter in terms of minute particles that combined to form larger bodies, whose properties could be changed by alterations in motion, size, or shape.

Boyle’s Death and Legacy

After the restoration of the British monarchy in 1660, Boyle was frequently in attendance at the court of King Charles II, and in 1662 he used his position to help the Royal Society obtain its charter. Boyle himself was one of the society’s charter members, and he was influential in the appointment of Robert Hooke as curator and Henry Oldenburg as secretary.

Boyle moved permanently to London in 1668, and his power and prestige increased still further as a result. He was offered a number of honors by the King, including a place in the House of Lords and even a bishopric, although he declined these on the grounds that he preferred the life of “a simple gentleman.”

Boyle was asked to become the Royal Society’s president in 1680, but he turned down this honor, too, stating that his conscience would not allow him to take the oaths that were required for the post. His religious beliefs were strong and consistent throughout his life, to the extent that one of the few positions he did accept was to govern the Corporation for Propagating the Gospel in New England.

Boyle was strongly of the opinion that religion and science were compatible and complementary to each other, and he wrote a large number of papers and essays in support of this view. He died on December 30, 1691, leaving a substantial sum of money in his will to promote Christianity.