Operation Barbarossa was the code name given by Nazi Germany to its invasion of the USSR during World War II. The largest military invasion in history, it comprised of more than four million Axis troops, stretched along almost two thousand miles of the Eastern Front. Although the Germans achieved some notable tactical victories during the operation, strategically it was a failure as the Nazis failed to capture Moscow. Barbarossa proved to be a turning point in the history of the war, and Germany never again threatened the Soviet capital.

Operation Barbarossa was the code name given by Nazi Germany to its invasion of the USSR during World War II. The largest military invasion in history, it comprised of more than four million Axis troops, stretched along almost two thousand miles of the Eastern Front. Although the Germans achieved some notable tactical victories during the operation, strategically it was a failure as the Nazis failed to capture Moscow. Barbarossa proved to be a turning point in the history of the war, and Germany never again threatened the Soviet capital.

Background

Even as far back as the 1920s, many members of the Nazi movement had seen it as a core objective for Germany to destroy the perceived threat presented by the communist-ruled Soviet Union. Large tracts of high quality land within the western USSR were also seen as ideal long-term locations for German settlements. After the Nazis came to power, Adolf Hitler”s government signed a non-aggression pact with the Russians in August of 1939. However, this was widely seen as being no more than a tactical ploy.

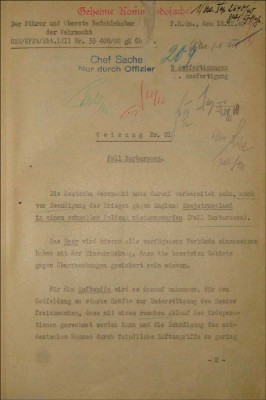

France and the Low Countries of Belgium, Luxembourg (occupation of Luxembourg), and the Netherlands were invaded by Germany in May of 1940. Two months later, Hitler resolved that the conquest of the Soviet Union would be his major objective in 1941. With this in mind, the Fuhrer signed an operational order for this in December of 1940. Officially, this was known as Directive 21, but it quickly became more widely known by its code name of Barbarossa, named after the 12th century Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa.

From the start, the plan was for German police and military units to fight a two-pronged war of destruction. Their first target was the communists who ruled the USSR. The second, as elsewhere in Europe, was to be Russian Jews. In the early months of 1941, Army High Command and Reich Security Main Office officials drew up plans for the deployment of special forces behind enemy lines, with specific orders to kill anyone—especially but not exclusively, Jews and communists—who was felt to be harmful to the aim of German occupation.

The Invasion

As the invasion began on June 22, 1941, the German army engaged in Operation Barbarossa was numbered at 217 divisions. Of these, 134 were intended for front-line duties, while 73 were to be engaged behind the front. Over three million of the Axis soldiers were German, with most of the rest coming from the allied states of Romania and Finland. Later on, smaller forces from Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, and Italy joined the assault, ranging along a front which stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

The build-up of German troops along the Russian border should not have come as a surprise, with the Soviets having been repeatedly warned about it by its western Allies. However, because of Josef Stalin”s refusal to act on these warnings, the Nazis had the tactical element of surprise when they attacked. A substantial portion of the USSR”s air force was still on the ground and was destroyed without even having the chance to take off. Meanwhile, vast numbers of Soviet soldiers were surrounded by German troops: with their supply lines severed, their only option was to surrender to the Germans.

Jewish Persecution and Genocide

While regular German army units spearheaded the advance into Russia, groups of police and SS followed behind, led by the SD and the Security Police”s Einsatzgruppen. These units were ordered to detect and destroy anyone who might be capable of organizing any resistance to the German advance, or later to the occupying forces. They were particularly active in murdering Jewish men and communist officials, although Roma people were also persecuted on a large scale. The surviving Soviet Jews were quickly rounded up and herded into newly established ghettos.

While regular German army units spearheaded the advance into Russia, groups of police and SS followed behind, led by the SD and the Security Police”s Einsatzgruppen. These units were ordered to detect and destroy anyone who might be capable of organizing any resistance to the German advance, or later to the occupying forces. They were particularly active in murdering Jewish men and communist officials, although Roma people were also persecuted on a large scale. The surviving Soviet Jews were quickly rounded up and herded into newly established ghettos.

From late July onward, representatives of Heinrich Himmler arrived at the Eastern Front. This gave the Nazis, aided by auxiliaries who were recruited from local sympathizers, an impetus to annihilate entire communities of Soviet Jews. At this point, the success that Barbarossa seemed to be enjoying led Hitler to decide on a new course. He ordered that German Jews should be deported to the USSR as the beginning of what would be known as the Final Solution of the Jewish Question: the utter destruction and mass murder of millions of European Jews.

Soviet Resilience

The first month and a half of Barbarossa saw enormous losses on the Russian side, but the Soviet Union held. By the middle of August, Soviet resistance was strengthening and it was becoming clear that Hitler”s initially ambitious timetable for Soviet defeat would not be met. Even so, six weeks later the Germans had reached the outskirts of Leningrad. Important industrial centers such as Dnepropetrovsk and Smolensk fell to the Nazis, who also flooded into the Crimean Peninsula. By the start of December, German troops had reached the outlying suburbs of Moscow itself.

Despite their spectacular advances, exhaustion had become a major problem for the German troops. The weather was closing in, and in the expectation of a rapid victory the men had not been properly equipped for the brutal Soviet winter. The Nazis had planned that their occupying forces would take food and farmland from the Russians, who would simply be left to starve on a massive scale. With this not achieved, the German troops had insufficient food, with medicine also in short supply. Their supply lines were also dangerously stretched, running for a thousand miles from Moscow back to Berlin.

Failure and Aftermath

The Soviets launched a major counter-attack on December 6, 1941, the day before the United States entered the war. The Russians succeeded in pushing the Germans back from Moscow, and by early 1942, their front had been forced back to near Smolensk. That summer, Germany mounted another offensive, aiming at the Caucasus oil fields and the strategically vital city of Stalingrad. In September, with Nazi troops barely 100 miles from the Caspian Sea, Europe was occupied by German forces to the greatest degree in the whole of World War II.

The Soviets launched a major counter-attack on December 6, 1941, the day before the United States entered the war. The Russians succeeded in pushing the Germans back from Moscow, and by early 1942, their front had been forced back to near Smolensk. That summer, Germany mounted another offensive, aiming at the Caucasus oil fields and the strategically vital city of Stalingrad. In September, with Nazi troops barely 100 miles from the Caspian Sea, Europe was occupied by German forces to the greatest degree in the whole of World War II.

The second German offensive also failed, with enormous casualties being sustained on both sides at Stalingrad, but the Soviets were able to hold the city. The USSR was in all-out war economy mode, and with Germany unprepared for a long, drawn-out campaign, the imbalance in production steadily increased. The Nazis tried one further attack at the Battle of Kursk in 1943, but when this failed there were no more attempts. After the heavy German defeat at Operation Bagration in summer 1944, the Soviets took less than a year to push their opponents back to Berlin itself, forcing the final Nazi surrender in May of 1945.