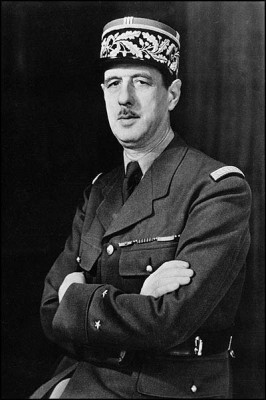

During World War Two, the Free French Forces consisted of both military units and individual people who pledged their allegiance to what was known as Free France. This was the name given to the resistance movement which had been set up by Charles de Gaulle during his exile in London in 1940. Its mission was to fight against the occupying Axis forces, and it rejected the terms of the armistice that Philippe Pétain had agreed to with the Germans on the fall of France. De Gaulle himself became one of France’s greatest military heroes for his leadership of the Free French.

During World War Two, the Free French Forces consisted of both military units and individual people who pledged their allegiance to what was known as Free France. This was the name given to the resistance movement which had been set up by Charles de Gaulle during his exile in London in 1940. Its mission was to fight against the occupying Axis forces, and it rejected the terms of the armistice that Philippe Pétain had agreed to with the Germans on the fall of France. De Gaulle himself became one of France’s greatest military heroes for his leadership of the Free French.

The Fall of France

Pétain became the leader of the French government on June 16, 1940. By this time the country’s situation was entirely desperate, and Pétain had come to the conclusion that there was no other course of action than to agree to armistice terms with the Germans. The following day, de Gaulle—who at the time had been a minister in the French government—fled to London. On June 18, he made a celebrated radio address (although at the time it was not widely heard) in which he called for patriotic French citizens to continue their struggle.

The British government granted recognition to de Gaulle on June 28, having officially accepted his claim to be Free France’s leader. From then onward, de Gaulle made use of his London base to co-ordinate a build-up of the Free French Forces. These did not amount to very much at first, being little more than a few units made up of volunteers of French citizens who had been living in Britain before the outbreak of the war. They were joined by a small contingent of the French navy which had managed to reach the northern side of the English Channel.

The Expansion of the Free French Cause

Fall of 1940 brought de Gaulle a significant boost, as a number of French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa, including Chad and Cameroon, declared their allegiance to the Free French cause. A number of lesser colonies in Asia and the Pacific quickly added their voices of support for the resistance. De Gaulle was dealt a notable and embarrassing blow, however, when in September of 1940 an attempt to take the Vichy-held naval base of Dakar ended in failure. This important center thereby remained occupied by Pétain’s so-called National Government.

Fall of 1940 brought de Gaulle a significant boost, as a number of French colonies in sub-Saharan Africa, including Chad and Cameroon, declared their allegiance to the Free French cause. A number of lesser colonies in Asia and the Pacific quickly added their voices of support for the resistance. De Gaulle was dealt a notable and embarrassing blow, however, when in September of 1940 an attempt to take the Vichy-held naval base of Dakar ended in failure. This important center thereby remained occupied by Pétain’s so-called National Government.

Free French forces had their first taste of action in an international operation in 1941, when they joined British operations in Egypt and Libya against the Italians. They also helped the United Kingdom to achieve victories in Lebanon and Syria, gaining a measure of revenge for their Dakar defeat by triumphing over forces loyal to Vichy. In September, the French National Committee was created. This was intended as the government in exile of Free France, and it was soon recognized as such by the Allied powers.

At this point, the Free French Forces were still rather small in numbers. However, by 1942 a domestic resistance movement had taken root in France itself. De Gaulle quickly saw the advantages of gaining the support of what was coming to be known as the French Resistance, and decided to rename his movement as the Fighting French Forces. The resistance was at that time somewhat fractured in terms of leadership, and de Gaulle dispatched Jean Moulin to France to attempt to form a unified front. By May 1943, he had come very close to succeeding in this aim, and the new National Council of the Resistance represented most of the major resistance factions.

De Gaulle and Giraud

In November of 1942, American and British forces launched a successful invasion of the western portion of north Africa. Large numbers of troops controlled by the Vichy government had been stationed there, but the Allied victory prompted the majority of them to defect to the Free French cause. The commander in chief of French forces in the area, backed by the Allies, was Henri Giraud, and he and de Gaulle were soon engaged in a power struggle.

In the city of Algiers in June of 1943, the French Committee of National Liberation was established. De Gaulle and Giraud were appointed to run the committee, with both men being named as joint presidents. However, de Gaulle’s political skills quickly allowed him to maneuver Giraud into a subsidiary role. In the spring of 1944, Giraud resigned, resulting in de Gaulle taking full control of the French war effort, other than in mainland France itself. His influence, personality, and clear ability led an increasing number of resistance organizations to declare that they saw their leader to be de Gaulle.

The Road Back to Paris

The major British-American Italian campaign of 1943 was supported by more than 100,000 Free French soldiers. This number had increased threefold by the first week of June 1944, when the invasion of Normandy was launched on D-Day. The Free French troops were now almost entirely supplied and equipped by the United States, giving them access to high quality weaponry and armor throughout their ranks for the first time since their initial founding in 1940.

The major British-American Italian campaign of 1943 was supported by more than 100,000 Free French soldiers. This number had increased threefold by the first week of June 1944, when the invasion of Normandy was launched on D-Day. The Free French troops were now almost entirely supplied and equipped by the United States, giving them access to high quality weaponry and armor throughout their ranks for the first time since their initial founding in 1940.

By August 1944, the Germans were being steadily pushed back in France, and the Free French First Army played an important role in the Allied drive. Later that month, the domestic resistance organizations, which had combined to form the French Forces of the Interior, provoked an uprising in Paris against the city’s Nazi occupiers. On August 26, de Gaulle made a triumphant return to the French capital, where he was greeted by vast crowds of cheering French citizens as his convoy drove down the Champs-Élysées.

The Free French Forces continued to play an important part in the liberation of the remainder of Nazi-occupied Europe. Indeed, by the spring of 1945 they constituted the fourth largest of the Allied armies, with their 1.3 million men under arms placing them behind only the Soviet Union, the United States, and Britain. De Gaulle himself, now considered a national hero, continued to play an important part in French affairs for the next quarter of a century. He was instrumental in the country’s withdrawal from Algeria in 1958, as well as the establishment of the Fifth Republic.