| Operation Husky | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Contenders | |||||||

| Military Leaders | |||||||

| Unit Strength | |||||||

| Initial Strength: 160,000 personnel 14,000 vehicles 600 tanks 1,800 guns Peak Strength: 467,000 personnel |

230,000 Italian personnel 60,000 German personnel 260 tanks 1,400 aircraft |

||||||

| Casualties and Deaths | |||||||

|

Total: 24,820 5,837 killed 15,683 wounded 3,326 captured |

Germany: ~20,000 casualties Italy: 131,359-147,000 killed, wounded and captured (mainly POWs) |

||||||

| Part of World War II | |||||||

Operation Husky was the code name given to the Allied invasion of the island of Sicily in World War II, which took place in the summer of 1943. The campaign ran from early July to the middle of August, and consisted of airborne and amphibious operations at first.

These were then followed up with land battles lasting around six weeks. The invasion was a success for the Allies, and their victory allowed them to use Sicily as a launchpad for the full Italian Campaign. Benito Mussolini, the dictator of Italy, was forced out of office by Hitler as a result of his defeat.

Background and Preparation

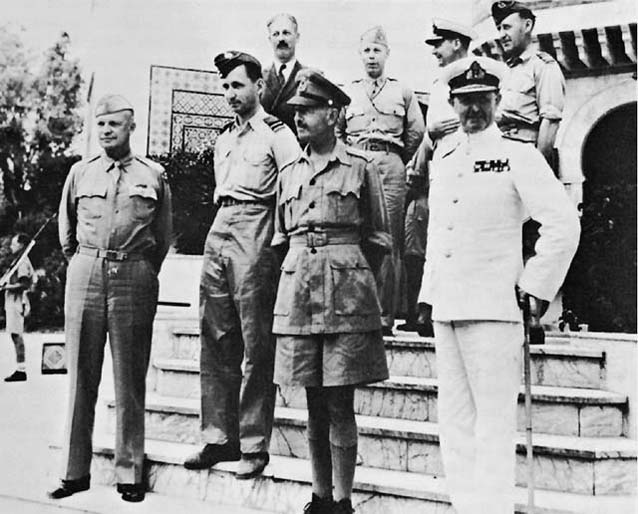

The main Western Allied powers – the United States, Britain, and the Free French – had met in Casablanca in January 1943. At this conference, Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed with Winston Churchill and General Charles de Gaulle an invasion of Sicily should be mounted later that year. Supreme command of the invasion was placed in the hands of the American general, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who oversaw the combined airborne and amphibious assault.

Before the main part of the operation began, there was a concerted bombing campaign of Italian targets, including some in Sicily. A more specific assault was also made on Pantellaria, a southern Italian island, and this was the first part of Italy to surrender to Allied forces. This occurred when the 1st Division of the British army landed on June 11. After this, the Allies paused for around a month to take stock of their positions and prepare for the main assault.

Operation Husky Begins

On July 9, Allied convoys came together near the British-held island of Malta, and from there they made for the southern coast of Sicily. The landing craft were slightly delayed in reaching the island because of a storm, but in fact this also helped the Allies: the Italian defense forces had been placed on a lower than usual state of alert because it was thought that the poor weather would have made an attack unlikely.

On July 9, Allied convoys came together near the British-held island of Malta, and from there they made for the southern coast of Sicily. The landing craft were slightly delayed in reaching the island because of a storm, but in fact this also helped the Allies: the Italian defense forces had been placed on a lower than usual state of alert because it was thought that the poor weather would have made an attack unlikely.

The first landings were made by the British, using more than 130 gliders of the 1st Airlanding Brigade. Their task was to take control of a bridge, the Ponte Grande, some distance to the south of Syracuse. However, the landings were fraught with problems: 200 men were drowned when their gliders crashed into the sea, many more landed in areas away from their target, and only 12 landed in the right place. Even so, the British were successful in taking and holding the bridge.

Meanwhile, American paratroopers were attempting a landing in another part of Sicily, but this operation, too, went far from smoothly. Many of the pilots used had little experience of combat and a combination of this inexperience, dust being thrown up from the dry ground, and fire from anti-aircraft guns meant that the U.S. paratroopers, more than 2,700, ended up quite widely spread, some landing as much as 50 miles away from their targets.

Amphibious Landings

The main assault on the Sicilian coast was a joint effort between British and U.S. forces, with American divisions attacking the western coasts and the British the east. Warships were based off the coasts in order to provide covering fire. The British forces had the easier time of the two groups, with relatively little fight being put up by the Italian defenders. This allowed the Allied guns and tanks to be landed quickly, and Panchino was in British hands by nightfall.

The main assault on the Sicilian coast was a joint effort between British and U.S. forces, with American divisions attacking the western coasts and the British the east. Warships were based off the coasts in order to provide covering fire. The British forces had the easier time of the two groups, with relatively little fight being put up by the Italian defenders. This allowed the Allied guns and tanks to be landed quickly, and Panchino was in British hands by nightfall.

Meanwhile, the U.S. divisions on the other coast of the island had a much harder time of things, with both Italian and German airplanes offering strong resistance to the invasion. Later in the afternoon, a Panzer division of heavy Tiger tanks joined the defense, but the Americans managed to land 18 Regimental Combat Team and the 2nd Armored Division by evening. The U.S. forces succeeded in holding their ground until covering fire from the Navy drove off the tanks.

Land Operations

The Axis were misled by the widely scattered Allied paratroopers into thinking that the invasion was on a massive scale, and requested reinforcements. However, these did not make a difference to the eventual outcome. On July 12, Augusta had come under British control, and General Bernard Montgomery ordered his men to mount an attack on Messina to the north. Lt. General George S. Patton, who commanded the American 7th Army, did not agree with this change in emphasis and told his troops to head west instead.

The U.S. soldiers advanced steadily toward Palermo, a strategically important seaport. They met relatively little serious resistance and, by the time they had occupied the port on July 22, more than 50,000 prisoners had been taken. Control of Palermo allowed the 9th Division of the U.S. Army to make a landing there, rather than having to repeat a riskier southern assault; it also opened up a useful supply line for the Allies. Once this had been achieved, Patton was ordered by Alexander to go forward to Messina.

The British 8th Army had things rather less its own way, with both stiff resistance from German paratroopers and the craggy Sicilian interior making progress difficult. The Germans were also aided by their 88mm anti-tank guns, but eventually the towns of Biancavilla, Catania, and Paterno were captured for the Allies. Meanwhile, Canadian forces under Lord Tweedsmuir’s command mounted a successful surprise assault on Assoro and Leonforte by climbing a cliff which seemed inaccessible and so had been left undefended.

Completion and Aftermath

By early August, Sicily was largely under the control of the Allies. American and British armies hurried to reach Messina first, with the Axis prevented from blowing up bridges by advanced airborne forces. The U.S. forces won the race to Messina by less than one hour, reaching it on the morning of August 17. They found that the German defenders had already been evacuated, but in such a rush that enormous caches of valuable fuel, guns, and ammunition were still present.

Messina itself had been largely ruined by Allied bombs and Italian defensive shells, but Operation Husky as a whole was a total success for the Allies. The goal of exposing what was known as Europe’s “soft underbelly” had been achieved, and the Mediterranean made secure for Allied shipping. Nevertheless, it was one of the bloodier contests of World War 2: casualties on the Allied side numbered about 25,000, while as many as 160,000 German and Italian soldiers were killed, wounded or captured.