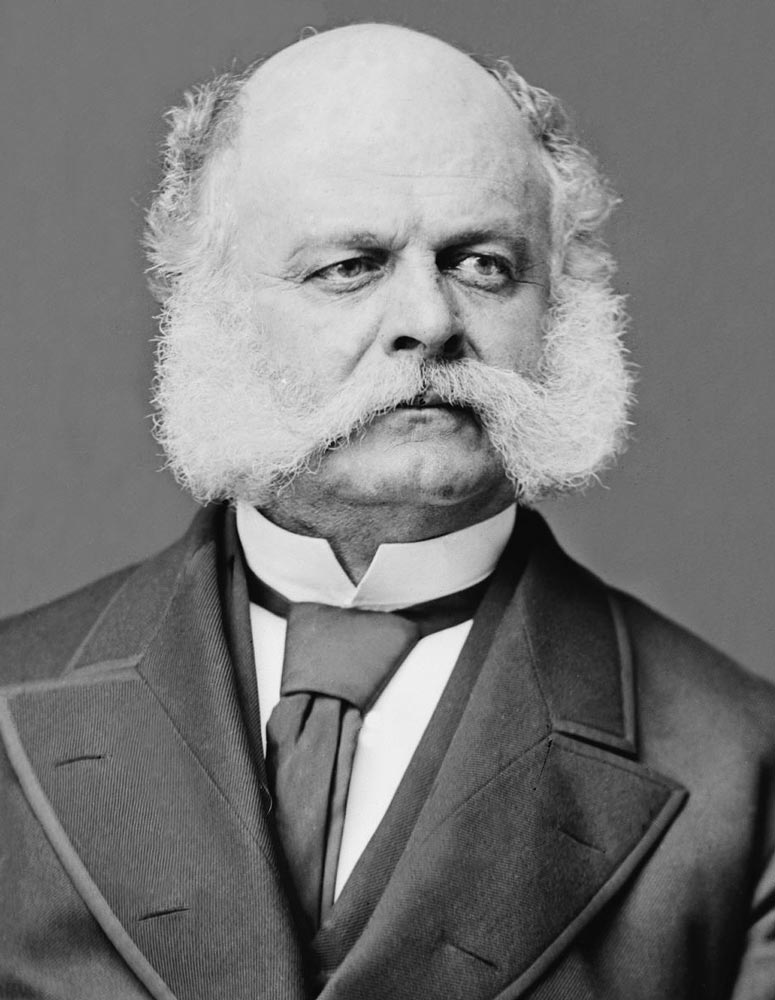

| Ambrose Burnside | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | May 23, 1824 Liberty, Indiana |

| Died | Sep. 13, 1881 (at age 57) Bristol, Rhode Island |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

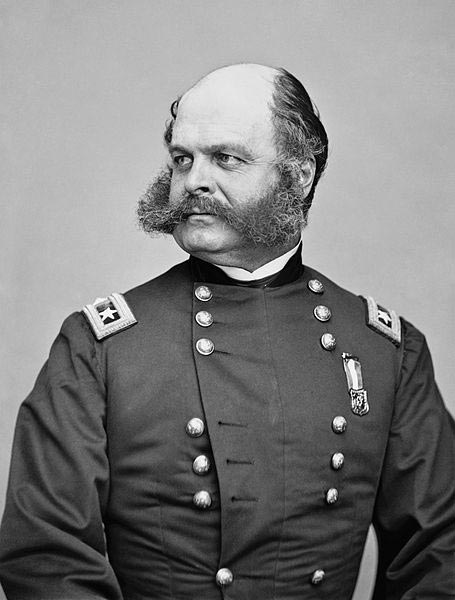

| Rank | Major General (1847–1865) |

| Battles/wars | Mexican-American War American Civil War: First Battle of Bull Run Burnside’s North Carolina Expedition Battle of Roanoke Island Battle of New Bern Maryland Campaign Battle of South Mountain Battle of Antietam Battle of Fredericksburg Knoxville Campaign Overland Campaign Battle of the Wilderness Battle of Spotsylvania Court House Battle of North Anna Battle of Cold Harbor Siege of Petersburg Battle of the Crater |

Ambrose Burnside (1824-1881) was a general in the United States Army during the American Civil War. He had a mixed record, enjoying substantial success in Carolina and Tennessee but suffering such severe defeats in two later battles that gave him a reputation for incompetence. After the war, he became a civil engineer and politician, rising to be a U.S. senator.

Early Life

Burnside was born in Liberty, Indiana, into a large family which eventually included eight siblings. He went to school at Liberty Seminary, but when his mother died in 1841, he dropped out of school and became a tailor’s apprentice. Rather than continue in this trade, Burnside used the political connections his father enjoyed to gain entry to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Here, he was a competent but unexceptional student, graduating almost exactly halfway up his class.

On his graduation, he was sent as a brevet second lieutenant to the 2nd U.S. Artillery. He was assigned to participate in the Mexican-American War at Vera Cruz but, by the time his unit arrived, the war had ended and so they were given garrison duties in Mexico City. On his return to the U.S., Burnside was placed under the command of Braxton Bragg – then a captain – on the Western Frontier. In this role, Burnside suffered a neck wound at the hands of the Apaches in New Mexico.

Out of the Army

In 1852, Burnside was sent to Fort Adams, Rhode Island, but in April of that year he married to Mary Bishop of Providence, and a year later he resigned his commission. He set up the Burnside Arms Company, which gained a contract to supply this gun to the U.S. Army. However, John B. Floyd, the Secretary of War, was bribed by another manufacturer and the contract was not honored. Burnside’s factory suffered a severe fire, and combined with the cost of his unsuccessful attempt to be elected a Congressman, this destroyed him financially.

Civil War

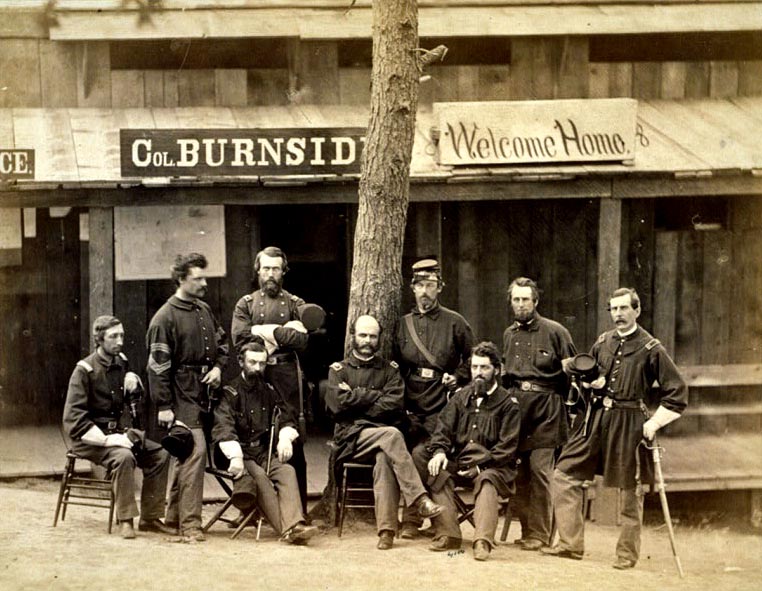

On the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Burnside was working as a railroad treasurer in Illinois, but once hostilities had begun, he went back to Rhode Island, raising a volunteer infantry regiment in that state; he was quickly named as its colonel. In that role, he took his men to Washington, D.C., and before long he had been appointed to command a brigade in northeast Virginia. He was a commander at the unsuccessful First Battle of Bull Run in July, but he endured criticism for the piecemeal way in which he had committed his troops.

After this reverse, the regiment Burnside had created was removed from service, with Burnside himself given a new role as brigadier general of volunteers. He underwent a period of training with the Army of the Potomac, and then set sail for North Carolina at the start of 1862. Burnside was more successful in this capacity, proving victorious at both Roanoke Island and New Bern. These victories brought him promotion to major general, and then – after McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign had failed – he was offered command of the Army of the Potomac by President Abraham Lincoln.

After this reverse, the regiment Burnside had created was removed from service, with Burnside himself given a new role as brigadier general of volunteers. He underwent a period of training with the Army of the Potomac, and then set sail for North Carolina at the start of 1862. Burnside was more successful in this capacity, proving victorious at both Roanoke Island and New Bern. These victories brought him promotion to major general, and then – after McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign had failed – he was offered command of the Army of the Potomac by President Abraham Lincoln.

Army of the Potomac

Burnside, however, rejected the offer on the grounds that he felt he was too inexperienced for such a role. He again declined command of the Army after the Union‘s second loss at Bull Run in August. This time, his IX Corps was sent to the Army of the Potomac itself, with Burnside commanding both his own and I Corps. Under the overall command of McClellan, Burnside and his men participated in both the Battle of South Mountain and the bloody Battle of Antietam.

At Antietam, Burnside was told to capture a bridge, but he was slow to react to events and did not think to look for other suitable crossings across the river, and this resulted in his forces suffering at the bridge itself. The slowness of Burnside’s reactions meant that the taking of the bridge was a protracted affair. Although it was eventually captured, by then it was too late for Burnside’s men to break out from the containment tactics practiced by Major General A.P. Hill.

At Antietam, Burnside was told to capture a bridge, but he was slow to react to events and did not think to look for other suitable crossings across the river, and this resulted in his forces suffering at the bridge itself. The slowness of Burnside’s reactions meant that the taking of the bridge was a protracted affair. Although it was eventually captured, by then it was too late for Burnside’s men to break out from the containment tactics practiced by Major General A.P. Hill.

Fredericksburg and Ohio

In early November, Lincoln persuaded Burnside to accept control of the army in place of McClellan, who had been removed after Antietam. Burnside’s idea to capture Richmond by circling around Lee via a quick push to Fredericksburg in Virginia was supported by Lincoln: the plan almost worked, but the late arrival of pontoon bridges meant that a river crossing was delayed. Instead, Burnside waited so long that Lee’s men arrived, and he suffered defeat in the Battle of Fredericksburg. After a first, unsuccessful attempt to resign, he was relieved of his command in January 1863.

The President, however, wished to retain Burnside and once again placed him in command of IX Corps, this time in Ohio. Burnside courted controversy in April after issuing an order making opposing the war a crime. As summer wore on, Burnside’s troops were closely involved in capturing rebel Confederate Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan. Later, Burnside’s offensive tactics won victories at Knoxville, Tennessee and Chickamauga.

Back to the East

After a successful engagement outside Knoxville in November 1863, Burnside was instrumental in the Union victory at Chattanooga. The early months of 1864 saw his IX Corps taken back east in order to help with the Overland Campaign of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, in which role Burnside at first reported directly to the general. Burnside’s troops took part in the Battles at Wilderness and Spotsylvania, but he tended to be overly cautious when committing his men and, overall, his actions lacked distinction.

After a successful engagement outside Knoxville in November 1863, Burnside was instrumental in the Union victory at Chattanooga. The early months of 1864 saw his IX Corps taken back east in order to help with the Overland Campaign of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, in which role Burnside at first reported directly to the general. Burnside’s troops took part in the Battles at Wilderness and Spotsylvania, but he tended to be overly cautious when committing his men and, overall, his actions lacked distinction.

The IX Corps later joined the siege at Petersburg, which had reached a stalemate. Burnside approved a plan by infantrymen of his IX Corps, in which they would dig beneath the Confederate lines and plant a huge bomb. This, on exploding, would produce a gap sufficiently wide to allow Union forces to attack. Burnside had intended to use specialist black troops but he was forced at short notice to replace them with whites. The Battle of the Crater in August turned out to be a terrible defeat, and Burnside was stripped of his command.

Aftermath

Burnside was put on leave and was never allowed to command troops again, his army days ending in April 1865. His legacy is of a man who was personally popular, both with his soldiers and with the common people, but an excessively promoted leader – a view shared by Burnside himself – who was often both incompetent and indecisive. When he returned to civilian life, he spent time in railroad management, then later enjoyed a distinguished political career as senator and governor. The distinctive style of facial hair known as sideburns is named in Burnside’s honor.