The Salem witch trials took place between February of 1692 and May of 1693. By the end of the trials, hundreds were accused of witchcraft, nineteen were executed and several more died in prison awaiting either trial or execution. While these events are referred to as the Salem witch trials, several counties in Massachusetts were involved, including Salem Village, Ipswich, Salem Town and Andover. While these were not the first examples of executions for witchcraft in New England, the volume of accusations and convictions generated one of the most infamous examples of mass hysteria in American history.

The Salem witch trials took place between February of 1692 and May of 1693. By the end of the trials, hundreds were accused of witchcraft, nineteen were executed and several more died in prison awaiting either trial or execution. While these events are referred to as the Salem witch trials, several counties in Massachusetts were involved, including Salem Village, Ipswich, Salem Town and Andover. While these were not the first examples of executions for witchcraft in New England, the volume of accusations and convictions generated one of the most infamous examples of mass hysteria in American history.

Puritan Superstitions

One of the primary contributing factors to the Salem witch trials was the superstitions prevalent in Puritan society. The belief that Satan was present and active was widely held in Europe and eventually spread to Colonial America. A common precept of this belief revolved around the necessity of believing in demons and evil spirits in order to confirm the belief of the existence of God and angels. This, combined with daily superstitions where all misfortunes were blamed on the supernatural, created a perfect environment for the mass hysteria leading to the Salem witch trials.

Village Relationships

Another factor likely contributing to the volume of witchcraft accusations revolved around the relationships within and between the various villages and towns. Numerous disputes occurred in Salem Village around items such as grazing rights, church privileges, and property lines. Many of the neighboring towns viewed Salem Village as problematic as evidenced by decisions such as hiring independent ministers to serve the village instead of supporting the larger Salem Town.

The Influence of the Church

In Puritan society, life revolved around the church. Most of the colonists in New England immigrated to the colonies due to religious strife in England and disagreement with the Protestant Church of England. Seeking a new home where they could build a society based on common religious beliefs, the Puritan settlers formed somewhat closed societies built around the church and related activities.

In the New England Puritan villages and settlements, all aspects of life revolved around the church. Residents were expected to adhere to the teachings of the church, such as attending lengthy sermons twice per week and avoiding activities deemed sinful, such as dancing, non-religious music, and celebrations of events or holidays rooted in Paganism, including traditionally religious holidays such as Christmas and Easter. Even children were affected by the restrictions of the church. Toys such as dolls were forbidden and all education revolved around the Bible and religious doctrine.

Evidence of Witchcraft

When it came to proving allegations of witchcraft, several types of evidence were considered during the trials. One type of evidence consisted of spectral evidence which encompassed the testimony of those who claimed to see an apparition or shape of the person afflicting them. While some argued that Satan could afflict anyone, others argued that Satan needed the permission of the person whose shape was assumed. Based on precedence in other cases, the courts ruled spectral evidence admissible in witchcraft trials.

When it came to proving allegations of witchcraft, several types of evidence were considered during the trials. One type of evidence consisted of spectral evidence which encompassed the testimony of those who claimed to see an apparition or shape of the person afflicting them. While some argued that Satan could afflict anyone, others argued that Satan needed the permission of the person whose shape was assumed. Based on precedence in other cases, the courts ruled spectral evidence admissible in witchcraft trials.

Effluvia also provided a significant source of evidence in witchcraft trials. The basis of this theory revolved around the concept that a witch would be affected by tests conducted on their victims. One common test was the witch cake where a cake was produced using specific ingredients including the urine of suspected victims. When the cake was fed to a dog, the person guilty of afflicting someone would cry out in pain, indicating guilt. Another common test based on effluvia was the touch test where a victim in the throes of a witchcraft induced fit would cease suffering when touched by the witch causing the affliction.

Other types of evidence included confessions of those accused and the direct testimony of an accused naming others as guilty of witchcraft. The presence of poppits, ointments or books on palm reading or astrology was also considered evidence of guilt. Finally, physical traits such as a mole or blemish, known as a “witch’s teat,” on the body also factored into decisions of guilt.

Early Accusations

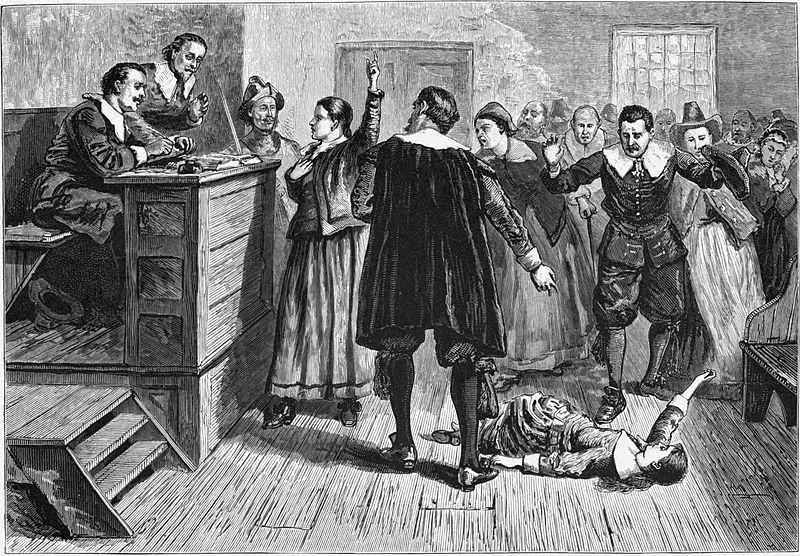

The combination of superstition, religious doctrine and subjective evidence all combined to produce an environment where accusations of witchcraft were easy to make and prove. In 1692, two young girls living in Salem Village began to experience fits where they screamed, threw things, contorted themselves into unusual physical positions and made strange sounds. They also complained of feeling pinches and pin pricks. Medical examinations found no evidence of physical illness or ailment. Soon after the first two girls showed symptoms, additional young women began showing similar signs.

As more young women exhibited signs of affliction, the first three accusations of witchcraft emerged. Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba were accused of performing witchcraft by those afflicted. Good was a homeless beggar likely accused because of her reputation. Osborne did not adhere to expected religious expectations such as regularly attending church meetings and sermons. Tituba was a slave of differing ethnicity. All three of the accused had significant differences from the rest of the villagers, making them easy targets for accusations.

Beginning March 1, 1692, the three accused were brought before local magistrates and questioned for several days before being jailed. After the initial accusations, additional ones flooded in, including accusations against upstanding church members who spoke out against the original accusations. This led to further worry and upheaval among the citizenry who had viewed their adherence to religious tenants as protection against evil. Membership and participation in church did not offer protection against accusations of witchcraft.

Once the accusations started, they quickly gained momentum. Over the course of a few months, the numbers continued to rise and more examinations began. At this point, accusations led to investigations and incarceration but no trial. It was not until May 27, 1692 when William Phips ordered the establishment of a Special Court charged with prosecution of the cases that further legal activity took place.

The Trials

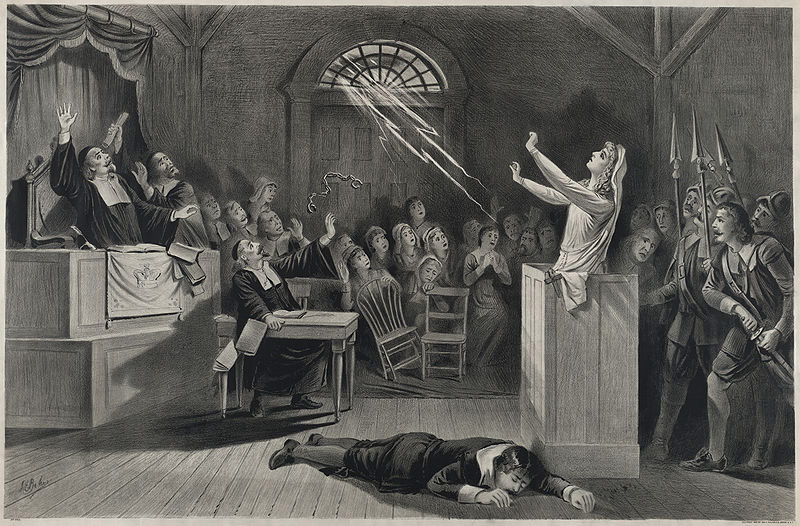

On June 2, 1692, the Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town to begin hearing the cases of those accused of witchcraft. William Stoughton, Lieutenant Governor, served as Chief Magistrate. Thomas Newton served as the Crown’s Attorney charged with prosecuting the cases. Stephen Sewall served as the clerk for the proceedings. Beginning immediately, the court issued indictments and began trial proceedings.

On June 2, 1692, the Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town to begin hearing the cases of those accused of witchcraft. William Stoughton, Lieutenant Governor, served as Chief Magistrate. Thomas Newton served as the Crown’s Attorney charged with prosecuting the cases. Stephen Sewall served as the clerk for the proceedings. Beginning immediately, the court issued indictments and began trial proceedings.

The first case brought before the court was that of Bridget Bishop. She was accused of witchcraft for not living the Puritan lifestyle and wearing appropriate clothing. Bishop was found guilty and executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

Following Bishop’s trial, other proceedings followed quickly. Over the course of five months, 22 additional guilty verdicts were returned. Of the 22, 18 were executed following their trial and conviction. Several more perished in prison either awaiting trial or execution. In October 1692, this court was dismissed by Governor Phips although many of the accused or indicted remained in prison.

In January 1693, the Superior Court of Judicature convened and began hearing the remaining cases. Between January and May of 1693, many were found innocent and released or had charges dropped. Of those found guilty by jury trial, the majority was pardoned and no more executions took place.

The Salem witch trials continue to be a subject of interest in many different ways. Influences affecting the trials are numerous, including the political climate, religious beliefs, and commonly held superstitions. Causes continue to be debated such as mass hysteria or biological explanations. Regardless of the cause of individual accusations, the Salem witch trials serve as an example of the impact of extremism, isolationism, and lapses in due process.