When the American Revolutionary War’s first battles began, the colonists did not have an organized, standing army. Before the Continental Army was formed, each individual colony had relied on a militia made of citizens, to provide local defense, or temporary regiments were used. Colonists had the desire to reorganize their militia, as tensions with Great Britain increased, and potential conflict was possible.

When the American Revolutionary War’s first battles began, the colonists did not have an organized, standing army. Before the Continental Army was formed, each individual colony had relied on a militia made of citizens, to provide local defense, or temporary regiments were used. Colonists had the desire to reorganize their militia, as tensions with Great Britain increased, and potential conflict was possible.

A national militia was proposed, but the First Continental Congress rejected this idea. The aversion to a standing army was an obstacle, but Congress realized that the war against the British would require organization and discipline in its defense. The colonies tried to reform their own militia, but the soldiers were often lightly armed, with very little training, and there was very little coordination between the states.

Formation of the Continental Army

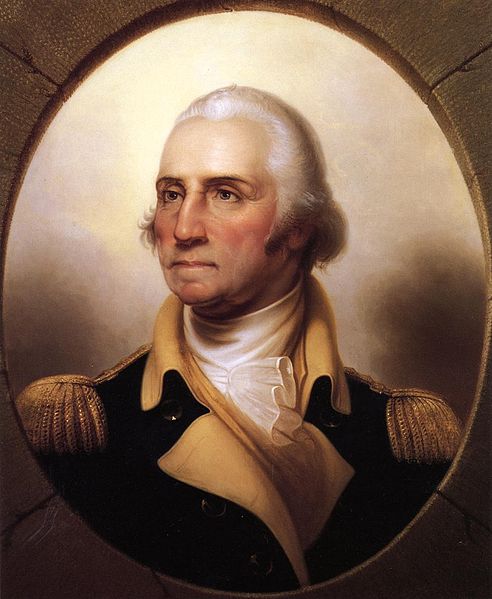

In April 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized organizing a colonial army of 26 company regiments. This state-motivated action was followed in turn by other New England states, and on June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress proceeded to establish a Continental Army for defense purposes. George Washington, a land surveyor with previous military experience, was elected Commander-in-Chief on June 15, 1775. With a plan in place, four major-generals and eight brigadier-generals were appointed.

In April 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized organizing a colonial army of 26 company regiments. This state-motivated action was followed in turn by other New England states, and on June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress proceeded to establish a Continental Army for defense purposes. George Washington, a land surveyor with previous military experience, was elected Commander-in-Chief on June 15, 1775. With a plan in place, four major-generals and eight brigadier-generals were appointed.

Army Criteria Set

The Continental Army was made up of troops from all thirteen colonies initially, and after 1776, all thirteen states contributed. The Second Continental Congress granted each state a specified number of regiments to serve under Washington’s command. The recruits would serve limited terms, and the newly formed army was paid for by the states in the form of recruitment bounties, or bonus payments for enlisting. These recruitment bounties could be in the form of land, cattle, cash, or a combination of all. The minimum enlistment age was sixteen, but with parental consent, those 15 years of age could also enlist.

Army Transformations

In 1775, the newly formed army consisted mostly of New England recruits, organized into three divisions, six brigades, and 38 regiments. In 1776, the army was reorganized, following the expiration of initial recruits. Washington asked to broaden the recruiting base, but it remained largely New England states, and consisted of 36 regiments and eight companies.

In 1775, the newly formed army consisted mostly of New England recruits, organized into three divisions, six brigades, and 38 regiments. In 1776, the army was reorganized, following the expiration of initial recruits. Washington asked to broaden the recruiting base, but it remained largely New England states, and consisted of 36 regiments and eight companies.

From 1777 to 1780, the invasion of massive British forces caused the Continental Congress to order each state to contribute one-battalion regiments, proportionate to their state’s population. Commander-in-Chief Washington was also given the authority to raise an additional sixteen battalions, and each recruit’s enlistment terms were extended, in order to avoid troop depletion before the war’s end.

In 1781 and 1782, the Continental Congress went bankrupt, and it was becoming difficult to pay for troops who had already served, and currently serving. It became primarily up to the individual states to pay for the Army, and the support for the war was at an all-time low. Congress eventually voted to cut all funding for the Army. In 1783 and 1784, as peace with Britain prevailed, the Continental Army was succeeded by the United States Army.

Serving Its Purpose

The Continental Army proved to be an effective force of defense. Despite monetary shortages, leaving troops without provisions, shelter, and sometimes basic supplies, the goal to defend was met. Many untrained, unskilled recruits fought through adversity to freedom. Now recognized as the precursor to the United States Army, the Continental Army evolved from colonists who were concerned for their own rights and freedoms, and continues today.