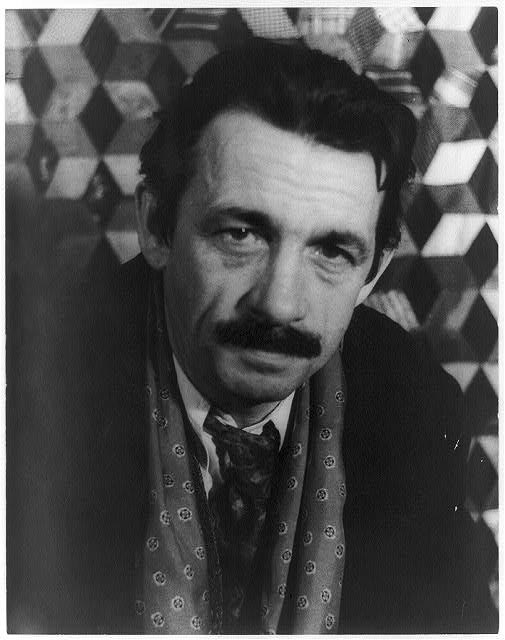

| Thomas Hart Benton | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Apr. 15, 1889 Neosho, Missouri |

| Died | Jan. 19, 1975 (at age 85) Martha’s Vineyard |

| Nationality | American |

| Movement | Regionalism, Social Realism, American modernism, American realism, Synchromism |

| Field | Painting |

| Works | View Complete Works |

Thomas Hart Benton was an American artist whose paintings and murals were extremely influential to the Regionalism movement during the first half of the twentieth century and provided a previously unheard of glimpse into life in Midwestern America. Regionalism is sometimes better known as American street painting, and refers to an artistic style devoted to realism in the depiction of American small towns, cities, and rural areas. Benton’s work was heavily focused on depictions of the Midwest. However, he lived in many areas throughout his life, both in America and abroad.

Early Life and Education

Benton was born on April 15, 1889, in Neosho, Missouri. His father was an influential politician who was elected as a U.S. Congressman four times. His uncle was a senator and Benton spent much of his early life in Washington, D.C.

While Benton’s family hoped that he would pursue politics and enrolled him in the Western Military Academy in 1905, hoping to groom him for this life, Benton had other plans. As a teenager he had worked as a cartoonist for a Missouri newspaper and decided to pursue his interest in art. In furtherance of this goal, he enrolled in the Art Institute of Chicago’s school in 1907. Two years later, he decided that he should move to Paris and study at the Academie Julian.

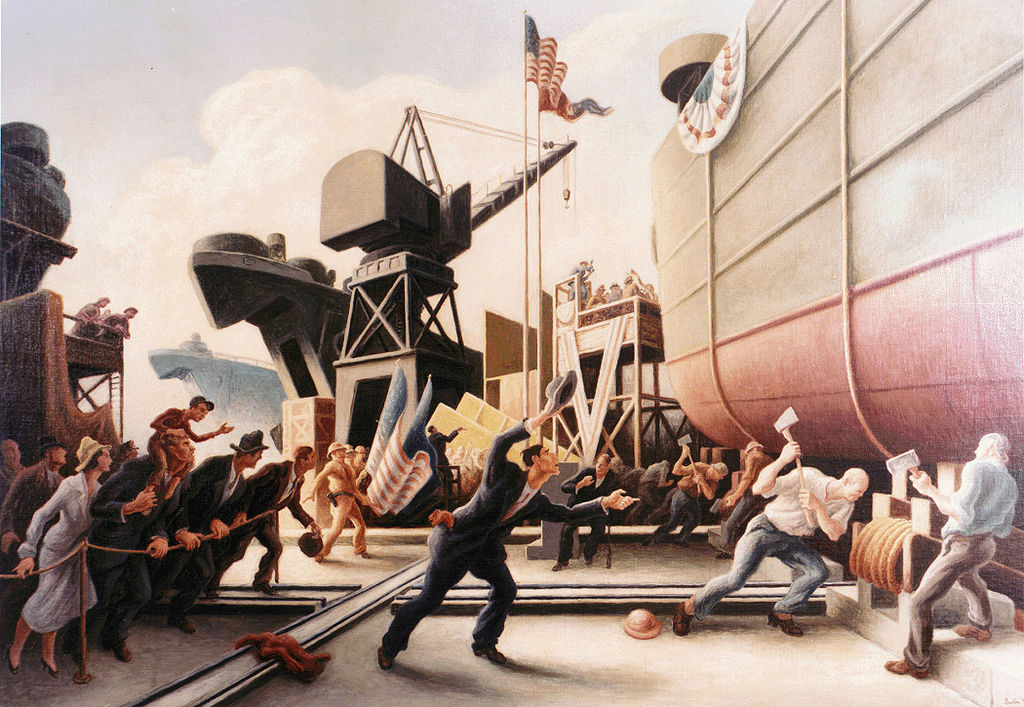

In 1913, Benton concluded his time in Europe and moved to New York City. He served in the Navy during World War II, and this proved to be a valuable experience in developing his artistic style. As part of his duties in the Navy, he drew pictures of camouflage ships that would come into the United States harbor. These pictures were used as records of United States ships and used to help if these ships were lost

In 1913, Benton concluded his time in Europe and moved to New York City. He served in the Navy during World War II, and this proved to be a valuable experience in developing his artistic style. As part of his duties in the Navy, he drew pictures of camouflage ships that would come into the United States harbor. These pictures were used as records of United States ships and used to help if these ships were lost

Benton returned to New York after the war and married Rita Piacenza in 1922. She was a student in an art class that he taught. Together, they had two children, and they remained married until Benton’s death on January 19, 1975.

Early Artwork and Beginning Career

In the early 1920’s, Benton declared his animus toward modernism, and began what would prove to be a lifelong push toward regionalism. He was a strong believer in naturalistic works, and was careful to try to give his paintings a more realistic feel. Among other things, Regionalism helped to build a bridge between abstract art and pure realism, and was highly influential in pop culture. Most importantly, however, it gave a voice to what “real America” was like and helped to illuminate corners of the country in ways that they had never been seen before.

Benton is best known for his murals. His first big commission was in 1932 when he was invited to paint murals of life in Indiana for the Century of Progress Exhibition that occurred in Chicago, Illinois, in 1933. Once he was aware of this commission, Benton commenced a thorough study of the history of Indiana, and even travelled extensively throughout the state seeking real people and situations to depict.

Benton’s murals proved to be extremely controversial. Some people did not enjoy that he portrayed real people engaging in the activities of everyday life; others were outraged at Benton’s frank portrayals of the Ku Klux Klan. Some view these murals as the first of a series of leftist political statements on Benton’s part. These murals and the subsequent controversy were instrumental in making Benton’s name known, and they currently hang at Indiana University.

Benton’s murals proved to be extremely controversial. Some people did not enjoy that he portrayed real people engaging in the activities of everyday life; others were outraged at Benton’s frank portrayals of the Ku Klux Klan. Some view these murals as the first of a series of leftist political statements on Benton’s part. These murals and the subsequent controversy were instrumental in making Benton’s name known, and they currently hang at Indiana University.

Around this time, Benton also painted a set of murals known as The Arts of Life in America for the Whitney Museum of American Art. These panels portrayed people engaged in typical cultural scenes.

Due primarily to these two sets of murals, Benton was featured in Time Magazine’s cover in late 1934. In this article, Regionalism was identified as a significant artistic movement. This was a triumph for Benton, who began to devote himself even more firmly to this artistic school as he moved back to Missouri in 1935.

The Triumph of Regionalism

Upon his return to Missouri, Benton was commissioned to create a mural. This work, titled A Social History of Missouri, is widely regarded as Benton’s greatest triumph. It was also extremely controversial, as Benton continued to incorporate social commentary and leftist political thinking into his work. Among the topics that he dealt with in this mural were slavery and Jesse James, Missouri’s most famous outlaw.

Benton used the late 1930’s to produce some of his best work, including an allegorical nude that he called Persephone. While this painting was considered vulgar by many of his contemporaries, Benton used the old myth to paint a picture of an older, dying generation who coveted the promise and youth of America’s new generation.

Later Life and Career

Later in Benton’s life he settled in Kansas City and taught at the Kansas City Art Institute. Benton’s work as a teacher is remembered for the ultimate influence that he had over Abstract Expressionism. In his long teaching career, he taught Jackson Pollock, who is widely regarded as the spearhead of this movement.

During the horrors of World War Two, Benton continued to be active in Regionalism. He created a series of prints called The Year of Peril, which were widely distributed. These prints were political in nature and portrayed the threats of fascism and Nazism.

After the Second World War, Benton remained active as an artist. However, Abstract Expressionism grew in popularity and Regionalism became nearly extinct. In this environment, Benton’s work ceased to have the element of social commentary that his early murals had expressed, and he turned primarily to painting farmlands in the preindustrial era.

Benton also continued to paint murals, and indeed, at his death in 1975, he was still at work in his studio attempting to complete his final mural, The Sources of Country Music.

Benton’s legacy lives on today, as his murals offer us a rare glimpse into the nuances of Midwestern American life in the early 1900’s as well as a powerful social commentary regarding America’s long history.