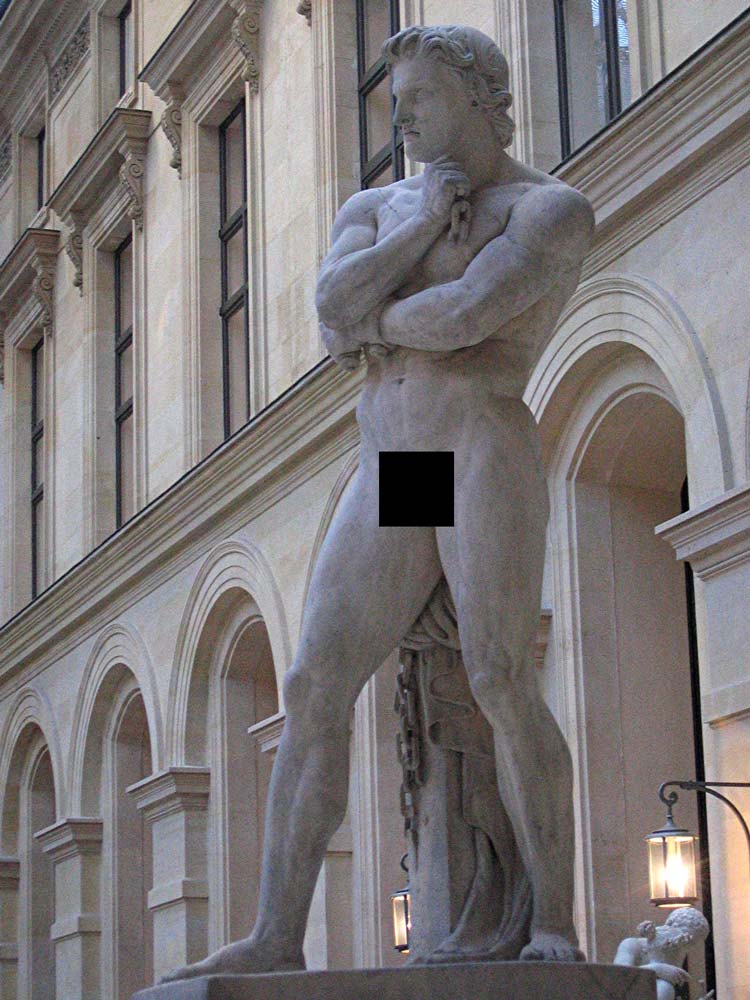

| Spartacus | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Slave Revolt Leader | |

| Born | c. 109 BC Around the middle course of Struma River |

| Died | 71 BC Battlefield near present territory of Senerchia |

| Nationality | Thracian |

| Wars | Third Servile War |

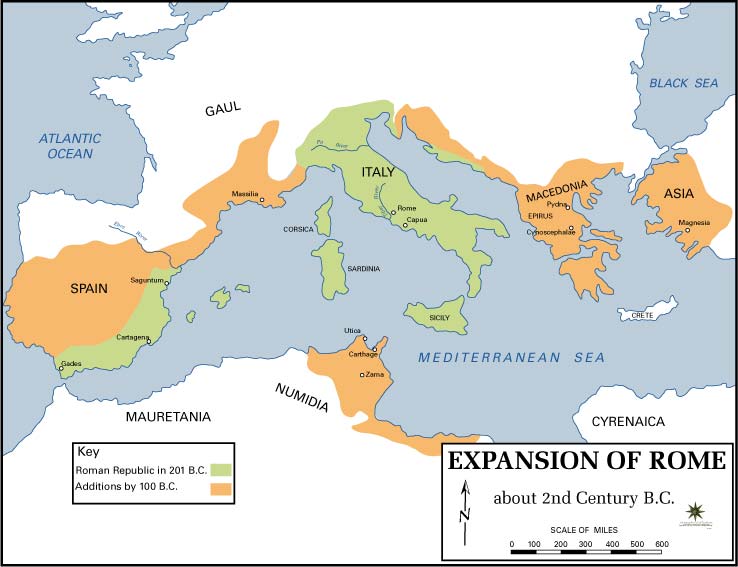

Spartacus (c. 109-71 B.C.) was a gladiator from Thrace, most famous as a leader in a major slave revolt. This uprising against the Roman Republic, commonly referred to as the Third Servile War, saw Spartacus joined by a number of Gauls in fighting against Roman dominance. Although relatively little is known about him beyond his role in the war, it is generally believed that he was a gladiator and that his military leadership was impressive.

Early Life

All the major contemporary sources for the life of Spartacus agree that he was a Thracian. Plutarch adds that he came from a Nomadic stock. The historian Appian states that Spartacus had at one time fought in the Roman army itself but later found himself imprisoned and enslaved. As a consequence, he was sold as a gladiator. According to Florus, the reasons for his enslavement included both robbery and desertion from the army, although further details are unknown.

It is thought that Spartacus came from the Maedi tribe, a people who inhabited the far southwestern part of Thrace, close to the border with Macedonia. His wife was a seer with the tribe, and according to Plutarch she was enslaved along with her husband. Spartacus’ name itself was not particularly unusual for a man from the area by the Black Sea, with a number of local kings having borne similar names, such as “Sparta” or “Sparadokos.”

Spartacus the Slave

After his enslavement, Spartacus trained at the gladiators’ camp close to Capua. By 73 B.C., it is known that he was beginning to plot a break-out, along with a number of his comrades. Although a large-scale escape was foiled when the plan was betrayed, a few dozen men did manage to escape, using kitchen knives as weapons. They eluded the men sent to recapture them, and after gaining recruits and plunder from the surrounding countryside, established a fortified position close to Mount Vesuvius.

After his enslavement, Spartacus trained at the gladiators’ camp close to Capua. By 73 B.C., it is known that he was beginning to plot a break-out, along with a number of his comrades. Although a large-scale escape was foiled when the plan was betrayed, a few dozen men did manage to escape, using kitchen knives as weapons. They eluded the men sent to recapture them, and after gaining recruits and plunder from the surrounding countryside, established a fortified position close to Mount Vesuvius.

Spartacus was chosen as one of the leaders by the escaped gladiators, along with Denomaus and Crixus, two Gaulish slaves. It is not entirely certain how command within the group operated, and the positions of the two Gaulish leaders as they related to that of Spartacus himself is unclear. It is possible that Roman sources tended to project their own view of military hierarchy when writing of the events of the revolt.

The Roman Response

The Empire was unable to respond as quickly and decisively as it might have liked, since the legions were occupied with putting down a Spanish rebellion and dealing with the Third Mithridatic War. In any case, Rome considered Spartacus’s revolt to be little more of a side-issue rather than a true problem. As such, only a militia force was sent. They sieged the rebellious slaves’ encampment, hoping to starve them out. Instead, Spartacus led his men down an almost sheer cliff and went around the back of the Romans, attacking them from their undefended rear and killing the majority of them.

The Empire was unable to respond as quickly and decisively as it might have liked, since the legions were occupied with putting down a Spanish rebellion and dealing with the Third Mithridatic War. In any case, Rome considered Spartacus’s revolt to be little more of a side-issue rather than a true problem. As such, only a militia force was sent. They sieged the rebellious slaves’ encampment, hoping to starve them out. Instead, Spartacus led his men down an almost sheer cliff and went around the back of the Romans, attacking them from their undefended rear and killing the majority of them.

A second Roman expeditionary force was also well beaten by the slaves, who killed the commander’s lieutenants and seized a substantial amount of military hardware. By now, the rebellion was so impressive that it found it quite easy to recruit more slaves to its cause. Even some of the local small farmers decided to join the revolt, and at their peak Spartacus’ troops numbered more than 70,000.

Tactical Ability

Spartacus had by now shown that he possessed considerable tactical acumen. Even though most of the slaves had no military experience at all, they were able to make good use of their unorthodox nature. By the early part of 72 B.C., they were frequently launching raiding parties as far afield as the towns of Nola and Thurii. At this point, the slave force had been split into two groups, one commanded by Crixus and one by Spartacus.

That spring, the slave force marched north, and the Senate – rattled by previous failures – sent two full legions to the area. At first the Romans had some success, defeating Crixus’s force of 30,000 men near Mount Garganus. However, Spartacus himself quickly revenged his partner’s failure and managed to defeat the legions himself. By now, Rome was becoming alarmed by the snowballing strength of the slave rebellion, and gave the hugely wealthy Marcus Licinius Crassus the task of putting it down.

The Third Servile War

Crassus was given command of a huge force of eight legions, comprising up to 50,000 professional soldiers. Discipline within the ranks was extremely harsh, with punishments even extending at one stage to decimation – the putting to death of every tenth man in a unit. For reasons which have never been fully established, Spartacus took his followers back to southern Italy for a few months; however, early in 71 he resumed the slaves’ northward push.

In response to Spartacus’ actions, Crassus placed six of his eight legions along the regional border, sending the other two under Mummius, his legate, to move around behind the rebel force. Mummius’ orders were not to fight, but he disobeyed them and his force was crushed. Despite this setback to the Roman cause, Crassus led his legions to several victories, pushing Spartacus southward once again. By late 71, the slave leader’s army had been forced back to an encampment close to the Strait of Messina.

Spartacus is then said to have agreed on a deal with local pirates to transport his men to Sicily, so that he could add to his forces. The pirates betrayed him and made off with the payment, and though there is some evidence that Spartacus attempted to build rafts, this did not come to anything. He was forced to retreat in the direction of Rhegium, hotly pursued by the Roman legions under Crassus. When the latter arrived, the legions constructed fortifications at the Rhegian isthmus, cutting off the supply line to the slaves.

Defeat and Death

At this point, Pompey’s legions came home from Spain, at which point the Senate ordered them to relieve Crassus. The latter was concerned that this would mean Pompey taking the credit for himself, and Spartacus saw an opportunity to negotiate. This initiative failed, and a part of the slave force was captured. This led to a collapse in discipline within the slave ranks, with infighting among small, autonomous groups of slaves. Spartacus turned to face the enemy for a final stand but was crushed: most of the slaves died on the field of battle.

Spartacus was believed to be among those who died in the last confrontation, even though his body was never found. The Romans, mindful of the fear that the revolt had prompted within their own people, decided to make the harshest possible example of the 6,000 slaves who had survived the battle. They were sentenced to crucifixion, and their crosses lined the route from Capua back to Rome along the Appian Way. Spartacus himself came to be remembered as a military leader who succeeded for a time against the almost overwhelming superiority, in training and discipline, of the Roman army.