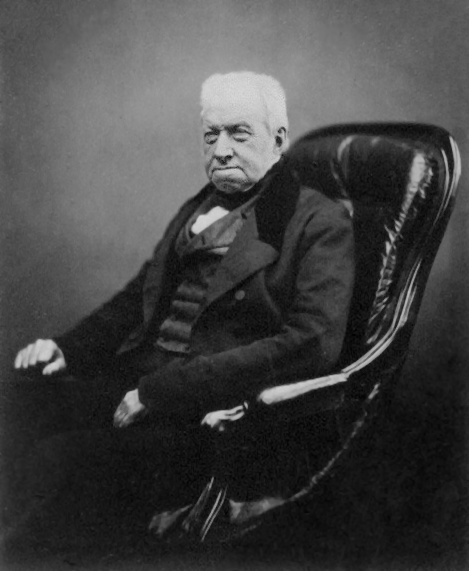

| Robert Brown | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Botanist | |

| Specialty | Botany |

| Born | Dec. 21, 1773 Montrose, Scotland |

| Died | June 10, 1858 (at age 84) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

Robert Brown, a famous botanist from Scotland, was a pioneer in the field of microscopy. He was one of the first botanists to completely describe the nucleus of cells while he also observed Brownian motion. He was also very influential in ‘paleobotany’, the study of primitive plant life.

Brown was one of the scientists on Matt Flinders’s expedition of discovery to New Holland. On his voyage, he gathered many plant samples. He classified them and named many of them. His number of botanical writings and articles made him a highly respected and admired scientist of the century.

Early Years

Robert Brown was born on December 21, 1773, at Montrose, Scotland. He went to school at Montrose where he studied art. After that, he studied medicine at the University of Edinburg but did not finish his education. He became very enthusiastic about botany, accompanying many botanists on field visits all throughout Scotland. After quitting the school in 1793, he joined the military and then he was posted as Surgeon’s Mate to Ireland. While there, he collected and researched Irish flora.

In 1798, when he was in London on military business, the Linnean Society accepted Robert as an associate. By now, he was unsatisfied with his army profession. He applied to be a part of Flinders’ journey to Australia and was given a place in 1800. Sir Joseph Banks demanded the Dublin Lord Lieutenant to discharge him from the military service, and eventually a deal was achieved whereby he continued being a commissioned man having an admiral’s income to aid his mother.

Brown’s Travels and Discoveries

Brown prepared for the trip by researching Australian flora which Banks had collected. As soon as he was in Australia, he collected extensively, although a lot of his specimens were misplaced when one of the ships was damaged in 1803. The next summer, he spent many months in New Zealand, although the majority of the plants he gathered ended up to have already been explained by others. Then, he made some other collections in and around Sydney, but was distracted by the unfavorable nature of the local residents.

In 1805, he returned back to England, devoting much of the journey attempting to keep his thousands of plant specimens free from the moist atmosphere which frequently threatened them. He was disappointed when in the middle of 1810, the publication of a monograph on Brown’s findings was displaced by Richard Salisbury.

However, in the same year, he made his primary work on the Australian flora, entitled The Prodomus – one of the most outstanding flora journals written and a spectacular record not just for the flora of Australia but in the beautiful art of botanical writing as well. The book still remains remarkable for its scientific rigor and the quality of writing.

Later Years

During the 1810s, Brown worked as librarian in the Linnean Society and served as its clerk and housekeeper. He quit the role in the early 1820s, after Banks died. Banks left Robert Brown an allowance per year and a rented a house in London. Then he was able to thrash out a contract with the trustees of the British Museum in 1827, by which Banks’ substantial collections would be kept at the museum but only under Brown’s supervision. They would also be held in a new department devoted completely to their conservation.

Brown was offered significant roles at both Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities, but he rejected to relocate from London, believing that he owed it to Sir Joseph Banks’ legacy to stay. In 1828, he was made the Linnean Society’s Vice President and continued to be in that post for the rest of his life, other than a short time from 1849 to 1853 when he served as the president.

Brown’s Legacy

Robert Brown is best appreciated for his remarkable scientific brilliance. He added a new dimension to the usage of microscope and developed new approaches to looking at plants as well as their various parts. Brown’s commitment heightened botany from what had formerly been just a hobby for people in to a focused, specialized branch of the science. He founded what is now called the Department of Botany in the Natural History Museum at London and he is still regarded as the best botanist of the century. He passed away at the age of 84, a bachelor, in 1858.