RMS Lusitania was a British ship, briefly the largest in the world, whose sinking by a German submarine in 1915 changed the tide of American opinion in World War I and eventually led to the United States’ entry into the war. The ship was an ocean liner on the transatlantic route between Liverpool and New York City. Named after an ancient Roman province, now a region of Portugal, the Lusitania was the largest ship in the world between its launch and the completion of its sister ship, RMS Mauretania.

RMS Lusitania was a British ship, briefly the largest in the world, whose sinking by a German submarine in 1915 changed the tide of American opinion in World War I and eventually led to the United States’ entry into the war. The ship was an ocean liner on the transatlantic route between Liverpool and New York City. Named after an ancient Roman province, now a region of Portugal, the Lusitania was the largest ship in the world between its launch and the completion of its sister ship, RMS Mauretania.

Background

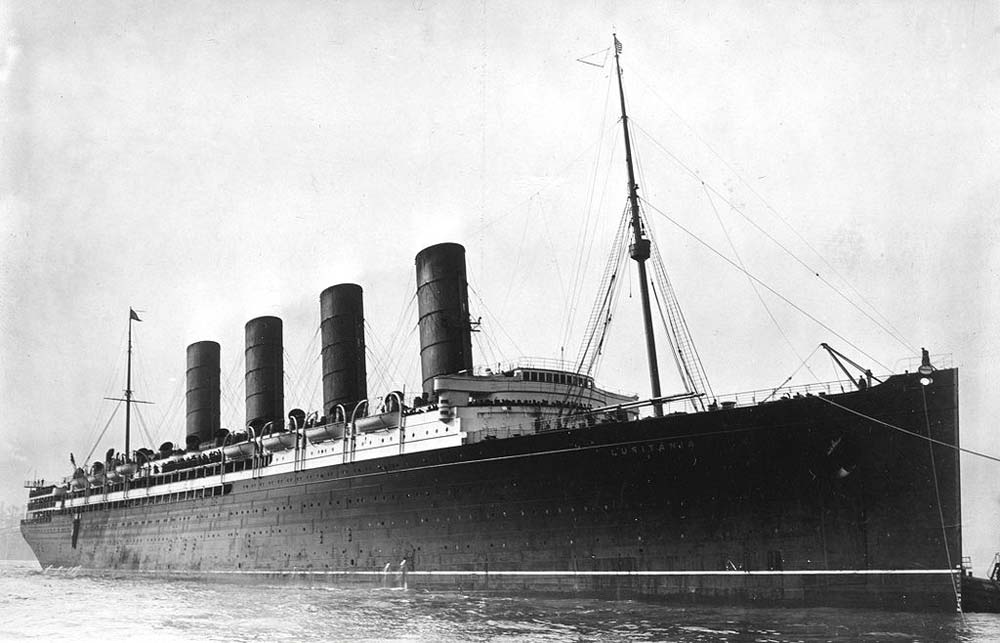

The ship was launched from John Brown’s shipyard in Clydebank, Scotland on June 7, 1906. She entered service with the Cunard line on August 26, 1907, becoming both the fastest and the largest ship anywhere in the world. Both these records had previously been held by ships from Germany, which at the time was a major rival of the United Kingdom in terms of maritime power. In the years before the outbreak of World War One, the Lusitania, together with the Mauretania and, later, the similar – but even larger – Aquitania provided a weekly service for passengers across the North Atlantic.

Early Wartime Service

During the war, Germany began to make use of unrestricted submarine warfare, a controversial move in which surface ships are not necessarily warned in advance of their sinking by submarines. RMS Lusitania, which had originally been built with modifications allowing her to be converted into a warship if necessary, was painted a dull gray at the outbreak of hostilities, in order to reduce her visibility to enemy vessels. However, within a short space of time, it became clear that the Royal Navy had the measure of its German counterpart and it seemed that British commercial shipping was safe. The Lusitania therefore continued in regular liner service.

During the war, Germany began to make use of unrestricted submarine warfare, a controversial move in which surface ships are not necessarily warned in advance of their sinking by submarines. RMS Lusitania, which had originally been built with modifications allowing her to be converted into a warship if necessary, was painted a dull gray at the outbreak of hostilities, in order to reduce her visibility to enemy vessels. However, within a short space of time, it became clear that the Royal Navy had the measure of its German counterpart and it seemed that British commercial shipping was safe. The Lusitania therefore continued in regular liner service.

During the winter of 1914/1915, demand for passenger shipping across the Atlantic fell sharply, and partly for this reason, a number of large liners were laid up in port. Others were converted into hospital ships or transports for troops. RMS Lusitania, however, remained in commercial operation, since even the reduced level of demand was enough to keep her operations profitable. Even so, a number of measures were taken in order to cut costs, such as the shutting down of one of her boiler rooms to save on coal and crew wages. The result of these measures was a slight reduction in the ship’s top speed – but her new 21-knot maximum was still higher than any other first-class liner remaining in service commercially.

The Sinking of RMS Lusitania

By 1915, it seemed as though most of the serious dangers to vessels of the Lusitania’s type had almost disappeared, and she was repainted in ordinary civilian livery, dropping the gray appearance she had earlier adopted. Even small aspects of her pre-war appearance were restored, such as the picking out of the name “RMS Lusitania” in gilt and the reversion of her funnels to the traditional Cunard colors. A bronze-colored band was added around the base of the newly white superstructure, but this was done purely for cosmetic reasons rather than because of any wartime contingency.

By 1915, it seemed as though most of the serious dangers to vessels of the Lusitania’s type had almost disappeared, and she was repainted in ordinary civilian livery, dropping the gray appearance she had earlier adopted. Even small aspects of her pre-war appearance were restored, such as the picking out of the name “RMS Lusitania” in gilt and the reversion of her funnels to the traditional Cunard colors. A bronze-colored band was added around the base of the newly white superstructure, but this was done purely for cosmetic reasons rather than because of any wartime contingency.

During the early spring of 1915, the ship operated with what appeared to be complete impunity in the busy North Atlantic shipping lanes, but in fact the German U-boat commanders had never ceased to regard her as a legitimate target. On top of this, at this early stage in the war, effective evasive action against a submarine attack had not fully been developed, making the Lusitania a fairly easy target. Added to this, the fact that the ship – and other liners – had been able to operate under relatively normal conditions in the region had led to complacency in some quarters, and a feeling that there was no real threat from German forces.

On May 7, 1915, the German submarine U-20 succeeded in getting close enough to launch a torpedo attack on the Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. The attack was a success, and two explosions on board the Lusitania – the second of which has never been fully explained (the ship was allegedly carrying ammunition, which the Germans argued was their reason for assaulting the ship in the first place) – resulted in the ship sinking no more than 20 minutes after the torpedo had first struck her. The disaster resulted in the loss of 1,192 lives, with a further four dying later as a result of injuries and trauma brought about by the sinking. Of the published passenger contingent of 1,960 people, fewer than 770 are known to have survived.

Aftermath of the Sinking

International public opinion was outraged by the sinking of RMS Lusitania, with many people considering it to be an inhuman act that had violated the laws and customs of war. Hostility toward Germany was markedly increased in Ireland and, which was to be of greater importance in the long run, the United States. In 1915, the U.S. administration of Woodrow Wilson was maintaining a policy of neutrality in the conflict. The sinking of the Lusitania resulted in agitation among many Americans for their country to enter the war on the side of the Allied powers; a declaration of war finally occurred on April 6, 1917.

Official inquiries were set up on both sides of the Atlantic into the causes of the sinking of the Lusitania. However, these – especially the British inquiry – were hampered by the requirements of official secrecy during a time of war. It was also thought important for propaganda purposes that Germany should bear the entire blame for the sinking, meaning that factors such as whether it had been wise to repaint the ship into its peacetime livery could not be openly discussed. Germany, meanwhile, took the view that Britain had left the Lusitania deliberately vulnerable, in the hope of pulling the United States into the war.

Germany insisted that RMS Lusitania had been carrying ammunition and other war-related supplies, and that as such she was not merely a civilian ship but one which could fairly be regarded as a legitimate target. The British government steadfastly denied this claim, putting it down to the Kaiser’s need to excuse a war crime to his own population, in order to maintain support at home for the war. It is only recently that divers on the wreck have discovered that the Lusitania was, indeed, carrying a certain amount of war contraband among her cargo.