| Oliver Cromwell | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Lord Protector | |

| In Power | 1653-1658 |

| Born | April 5, 1599 Huntingdon |

| Died | Sept. 3, 1658 London |

| Nationality | English |

| Religious Affiliation | Puritan |

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) was the Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Ireland and Scotland. He was a well known military and political leader of the 1600s. Cromwell was born in Huntingdon to Robert Cromwell and Elizabeth Steward. His family was of mid gentry class and was, at one time, one of the most wealthy in the area. However, since Robert was the youngest out of the siblings, his wealth was limited to a house and a bit of land. This gave him income that would make him considered one of the lower earning gentries.

Early Life

Cromwell studied at Huntingdon Grammar School and later attended Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge. He left without a degree after his father’s death in 1617. It has been said that he studied law in London. However, no records of him have been found in Lincoln’s Inn, the institution he most likely attended. Cromwell left school to support an expanding family—his widowed mother with his seven sisters and later his wife and their children. Cromwell made a living by farming and collecting rent from tenants using their little land. He lived an obscure early life at the bottom of the gentry class.

Despite his considerably low standing, Cromwell was still able to rub shoulders with very influential people. His grandfather, who was a knight during his time, lived just outside Huntingdon. Cromwell would frequently visit his grandfather’s estate and entertain powerful members of the court. His wife’s father was also an influential figure and was able to introduce Cromwell to leading Puritan figures. During 1637, Cromwell’s uncle passed away without heirs. This gave him a modest inheritance and some land to help support his family.

Religious Crisis

Between 1620 and 1630 Cromwell suffered what we would call today a mental breakdown. He was battling a personal crisis that had a lot to do with his religion. He sought treatment for depression and was observed to have been exchanging letters with an Arminian minister. During this time, he underwent a powerful religious conversion, turning to Puritanism, afterwards believing that God wanted to use him for a mission.

Parliament

During 1628, Cromwell was sponsored by the Montagu family and elected into the house of commons for Huntingdon. During this time, he made only one speech which was not received well. He made very little impact during the short stay. He was also probably the poorest member of parliament during the time. He owed this position to aristocratic connections rather than any good merit on his part. He seemed to have been overwhelmed by his status, and made very little contribution. When parliament dissolved because of Charles I, he went back to farming.

During 1628, Cromwell was sponsored by the Montagu family and elected into the house of commons for Huntingdon. During this time, he made only one speech which was not received well. He made very little impact during the short stay. He was also probably the poorest member of parliament during the time. He owed this position to aristocratic connections rather than any good merit on his part. He seemed to have been overwhelmed by his status, and made very little contribution. When parliament dissolved because of Charles I, he went back to farming.

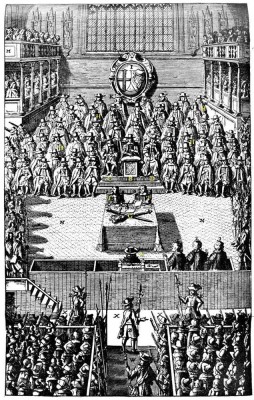

Charles I ruled without parliament for eleven years until the Bishop Wars. This was a Scottish rebellion where Charles I faced a shortage of funds which lead to a re-opening of Parliament in 1640. During this time, Cromwell was elected into Parliament, now representing Cambridge. He was a very outspoken member and he did not hesitate in criticizing royal policies as well as the rules of the established Anglican Church. He also had many advocacies regarding the power of the Parliament. Cromwell wanted annual Parliamentary meetings and for the Parliament to have power in naming army generals instead of the king.

Military Leader

Cromwell was more known as a military leader than a politician. Though he had no training or exposure during his life, he grew up around horses. His experience as a landowner gave him knowledge about these animals. He was convinced that if he could produce a very disciplined army, he would be able to defeat the Cavaliers of Prince Rupert. When the fighting broke out, he was appointed as captain of horse in 1642. His leadership qualities were recognized and within a year he moved up in rank, being named Lieutenant General of Horse for the Army of the Eastern Association.

The three largest parliamentary armies were combined and leaders could not agree upon a number of things. During the year 1645, the Parliament could not decide who they wanted to lead their armies, so they appointed Cromwell as a temporary commander. This was only supposed to last for forty days, yet it was renewed many times. In the year 1647, Cromwell permanently became commander of the cavalry. Cromwell trained his army to stay together after charge and not to aim at individual targets. This helped the men stay together and charge at the Cavaliers repeatedly. Cromwell had a natural instinct to lead and train his men. This led them to a lot of victories. He relied on pressing forward, giving his army an impact, rather than counting solely on firepower.

The First English Civil War

In late 1642 an armed conflict between the Parliament and Charles I was sparked by the failure to resolve any of the issues from before the Long Parliament. Cromwell relied on soldiers that were recruited by landowners who believed in their cause. It was not until three years later that Cromwell took over the cavalier and the Parliament appointed a new army of 22,000 professional soldiers under their commander-in-chief General Thomas Fairfax. This was known as the New Model Army.

The cause behind the conflict was seen as political and religious. During the first civil war, Cromwell was able to create innovative military techniques that helped him in his success. Close-order cavalry formations were introduced during this time, which meant that the troops rode knee-to-knee. Cromwell claimed that his military success was in favor of God’s will. He was an effective leader and was able to lead his men into victory, using various tactics. This was something impressive for someone who had no formal military training. It was said that he had skill to back up his courage he also trained his men with discipline on and off the battlefield.

The Battle of Marston Moor

The troop rode on to take part in the Battle of Edgehill, but they arrived too late. They were then recruited to be a full regimen for the winter of 1642-1643. They fought under the Earl of Manchester as part of the Eastern Association. The Battle of Marston Moor took place in July 1644 where Cromwell’s had risen in rank, still under Manchester. This battle was a significant part in Parliamentary victory, most notably, when the cavalry of Cromwell attacked the infantry of the Royalists from the rear at Marston Moor.

Cromwell was slightly injured during the battle and had to step aside for a while in order to tend to his neck wounds. His nephew had died in Marston Moor and this was the time he wrote the famous letter to his brother-in-law. He praised God throughout his moving letter which told of how his brother-in-law’s eldest son died. Though Cromwell’s troops were able to secure a large portion of North England during this time, they still failed to end the resistance of the Royalists. During this time, the war showed no signs of ending.

The New Model Army

The men who were members of The New Model Army received formal military training under the command of Cromwell. They were very disciplined, unlike the cavalry of Prince Rupert. It was said that after charging Prince Rupert’s troops would head off in different directions, trying to attack enemies one at a time. This gave them no force and no chance to charge again. Many of his horsemen could not return to the battlefield and the horses could not mount men any longer. The New Model Army was taught discipline, skill and courage under the leadership of Cromwell.

The men who were members of The New Model Army received formal military training under the command of Cromwell. They were very disciplined, unlike the cavalry of Prince Rupert. It was said that after charging Prince Rupert’s troops would head off in different directions, trying to attack enemies one at a time. This gave them no force and no chance to charge again. Many of his horsemen could not return to the battlefield and the horses could not mount men any longer. The New Model Army was taught discipline, skill and courage under the leadership of Cromwell.

The process of promotion in the New Model Army was not similar to that of the past. Unlike traditional armies, you could not receive a higher position or rank just because you came from a wealthy or powerful family. Men were promoted based on performance and skill. This gave the men more discipline and greater motivation. For the first time, working class men were allowed to become officers in the army. Cromwell wanted to make sure that the men who fought with him shared his values, believing that God was on their side. They would often sing Psalms and songs of praise before they went into battle.

The Battle of Naseby

The turning point of the war was marked by the Battle of Naseby. During the 1645 battle, The New Model army tore down the King’s troops. Cromwell led his army to great success, rerouting the Royalists once again. After this battle Charles I was not able to put forth an army that was powerful enough to face the Parliamentary army.

Charles I saw defeat in all battles after this one. It was the Battle of Naseby and Langsley that drained the King of any hope. When he realized that there was nothing left to do, he fled to Scotland in January of 1648 where he was captured and handed over to the Parliamentary army. He was imprisoned in Hampton court, yet he managed to escape during November that same year. He convinced the Scots to fight on his side, and he was able to raise another army. Soon enough, Cromwell’s army defeated the Scots and Charles I was taken prisoner.

Leadership and Puritanism

Cromwell leaned towards tolerance, yet debates and the King’s escape from Hampton hardened his heart. He became very vocal about supporting regicide. Many of his speeches and letters were heavily influenced by scripture. He was known to cite verses and include gospel meanings in his speeches. Cromwell used Puritanism to lead his men and discipline his army. He believed that God was actively directing him and his army. He believed that his army was God’s instrument and that the king was an unlawful authority in the eyes of the Lord. In a letter to Oliver St John, he urges St John to read the book of Isaiah, particularly the eighth chapter. In the verse it was said that only the godly will remain standing while the kingdom falls.

Cromwell leaned towards tolerance, yet debates and the King’s escape from Hampton hardened his heart. He became very vocal about supporting regicide. Many of his speeches and letters were heavily influenced by scripture. He was known to cite verses and include gospel meanings in his speeches. Cromwell used Puritanism to lead his men and discipline his army. He believed that God was actively directing him and his army. He believed that his army was God’s instrument and that the king was an unlawful authority in the eyes of the Lord. In a letter to Oliver St John, he urges St John to read the book of Isaiah, particularly the eighth chapter. In the verse it was said that only the godly will remain standing while the kingdom falls.

The Commonwealth of England

Oliver Cromwell established the Commonwealth of England shortly after the execution of Charles I. During this time, Cromwell tried to reunite a group known as the “Royal Independents.” He was closely associated with this group, but this broke out just before the war in 1642. He was, however, able to persuade St John into taking a seat in parliament. Meanwhile, the Royalists had regrouped to Ireland after they had signed a treaty with the Irish. Cromwell faced mutinies and rebellions during this time. He later left Bristol and stayed in Ireland for a while.

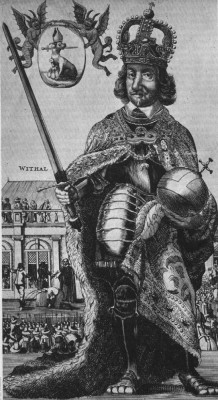

The Lord Protector

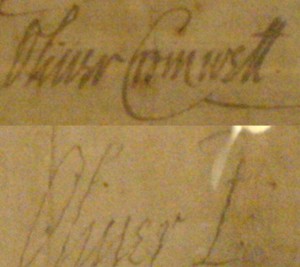

England saw the Rump Parliament dissolve and the establishment of the Barebones Parliament, which was set up by a preacher. John Lambert put together a new constitution which was known as Instrument of Government. During this time, Cromwell was named Lord Protector in a ceremony where he wore black, instead of monarchical regalia. He signed his name as “Oliver P,” the P standing for Protector. This was much like how monarchs used R for Regina. He was soon referred to as “Your Highness” and remained Lord Protector until his death in 1658.

Death

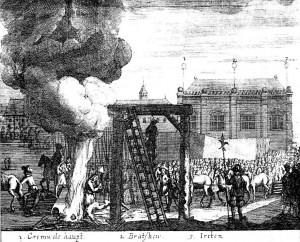

In 1658, Oliver Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard, to take his place as lord protector of the Commonwealth of England. He died later that year. His son did take his place, but not until the following year, 1659. However, government officials forced him to resign from his position. The restoration of the monarchy lead to necessary constitutional adjustments. Charles II was released from exile and was invited back to be king of the new monarchy. Cromwell’s remains were removed from Westminster Abbey then chained and hanged at Tyburn. His head was said to be put on display at the top of a pole of Westminster Hall. It remained there for twenty five years.

In 1658, Oliver Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard, to take his place as lord protector of the Commonwealth of England. He died later that year. His son did take his place, but not until the following year, 1659. However, government officials forced him to resign from his position. The restoration of the monarchy lead to necessary constitutional adjustments. Charles II was released from exile and was invited back to be king of the new monarchy. Cromwell’s remains were removed from Westminster Abbey then chained and hanged at Tyburn. His head was said to be put on display at the top of a pole of Westminster Hall. It remained there for twenty five years.