The Enrollment Act of 1863 is the name given to the law which enabled the military draft to be used on a federal scale in the United States for the first time – although the Confederacy had instituted conscription the previous year. It was passed during the Civil War, at a time when the North had suffered a series of defeats and was short of men. The act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on March 3, 1863.

The Enrollment Act of 1863 is the name given to the law which enabled the military draft to be used on a federal scale in the United States for the first time – although the Confederacy had instituted conscription the previous year. It was passed during the Civil War, at a time when the North had suffered a series of defeats and was short of men. The act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on March 3, 1863.

Scope of the Act

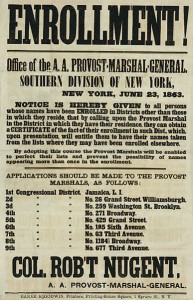

The act mandated the enrollment of all male citizens and would-be citizens aged between 20 and 45. Each congressional district was assigned, by federal agents, a certain tally of new soldiers that must be enlisted. Once this number had been established, the task of filling the quota – through both drafted men and volunteers – fell to the states. For a variety of reasons, the states preferred to enlist volunteers, with these men being given bounties of at least $100 to join up. The scale of the payments from federal, state, and local level became so great that some men were tempted into “bounty jumping”, whereby they would repeatedly sign up, take the money, and re-enlist in another place with the intention of repeating the process.

For these reasons, the number of soldiers who fought as conscripted men was in fact fairly small. This meant that the practice of conscription had relatively little impact militarily; however, it was much more important on the social level. Racial and class divisions were starkly revealed by the act’s operation, with the most serious opposition to the act being seen in New York City. The city contained substantial pockets of people who sympathized with the South, among them a large part of the Irish community. These people were worried that, if the North won the war and abolished slavery throughout the country, Irish workers would be out-competed for jobs by newly free blacks.

The Act Becomes Official

Further opposition came from the fact that it was possible for the rich to effectively buy their way out of conscription by substituting other men in their place. Both the Enrollment Act itself and the Emancipation Proclamation, which had been passed at about the same time, were opposed by many Irish-Americans. On July 4, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York State, gave a speech which castigated the practice of conscription as unconstitutional. He further alleged that there was a partisan element to the practice, with Democrats being disproportionately picked out for the draft as compared to Republicans.

Further opposition came from the fact that it was possible for the rich to effectively buy their way out of conscription by substituting other men in their place. Both the Enrollment Act itself and the Emancipation Proclamation, which had been passed at about the same time, were opposed by many Irish-Americans. On July 4, Horatio Seymour, the Democratic governor of New York State, gave a speech which castigated the practice of conscription as unconstitutional. He further alleged that there was a partisan element to the practice, with Democrats being disproportionately picked out for the draft as compared to Republicans.

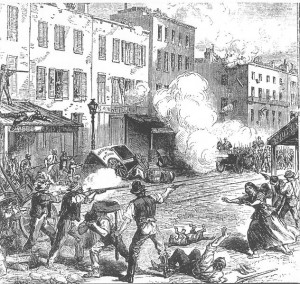

On July 12, one day after the first draftees had been called, violent riots broke out in New York, with government offices burned to the ground and communications lines severed. Rich citizens were singled out for attack, as were black people and any businesses that employed them. Many black residents were beaten and some were lynched. The authorities did not regain control of the city for over a week, in which time more than a hundred people had died. However, despite riots in a few other cities, in general the act was complied with. This was substantially because the bounty system, while imperfect, did ensure that the Union army remained mostly volunteers throughout the Civil War.