The first major military initiative of the Revolutionary War was the invasion of Quebec, Canada by American forces. The purpose of the campaign was to capture Quebec and convince the French speaking colonists to join the thirteen colonies in revolt against the British Empire, which would strengthen the position of the rebels in the western seaboard of the continent.

The first major military initiative of the Revolutionary War was the invasion of Quebec, Canada by American forces. The purpose of the campaign was to capture Quebec and convince the French speaking colonists to join the thirteen colonies in revolt against the British Empire, which would strengthen the position of the rebels in the western seaboard of the continent.

The Battle of Quebec was fought early in the Revolutionary War. The American commanders included Major General Benedict Arnold and Brigadier General Richard Montgomery, both leading a raiding force of roughly 1,200 men to capture Quebec City from the small British garrison and Canadian conscripts stationed there. It took place on December 31, 1775 and ended in a major defeat for American forces.

The March

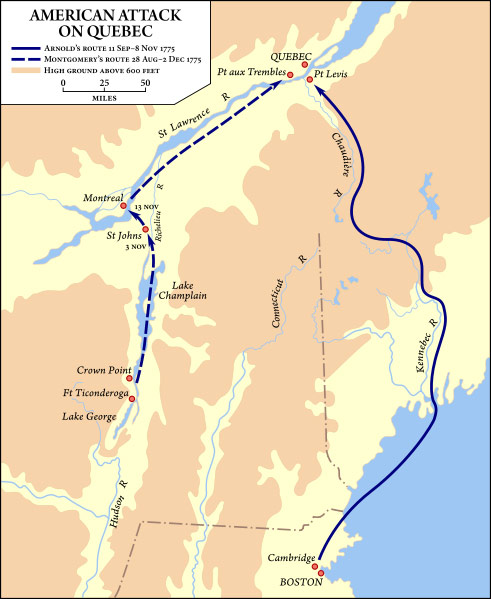

The foundation for the battle had been laid in the capture of the fort of Ticonderoga, a key defensive location, which was swiftly followed by the capture of Montreal and the near capture of a senior British General, Guy Carleton. The force which eventually fought in the battle at Quebec City was a combination of troops which has previously marched on Montreal, led by Montgomery, and the second column under the command of Arnold which had marched from Boston through the wilds. It is of particular note that the long march of Arnold’s troops through the cold Maine winter wilderness left his troops on the brink of starvation and lacking in virtually all supplies. Only half of the 1,000 men who left Boston took rank on the field.

The foundation for the battle had been laid in the capture of the fort of Ticonderoga, a key defensive location, which was swiftly followed by the capture of Montreal and the near capture of a senior British General, Guy Carleton. The force which eventually fought in the battle at Quebec City was a combination of troops which has previously marched on Montreal, led by Montgomery, and the second column under the command of Arnold which had marched from Boston through the wilds. It is of particular note that the long march of Arnold’s troops through the cold Maine winter wilderness left his troops on the brink of starvation and lacking in virtually all supplies. Only half of the 1,000 men who left Boston took rank on the field.

Arnold’s column arrived before the rest of the force and failed to extract surrender by messenger, indeed the messengers were set upon by cannon fire. The starved soldiers lacked artillery, ammunition, and half the strength with which they left Boston. They were forced to resort to a blockade of the Western road to the city. After some days they were forced to retreat in fear of a British counterattack. In their retreat they positioned at Pointe-aux-Trembles, and there they sat awaiting the arrival of Montgomery.

The Battle

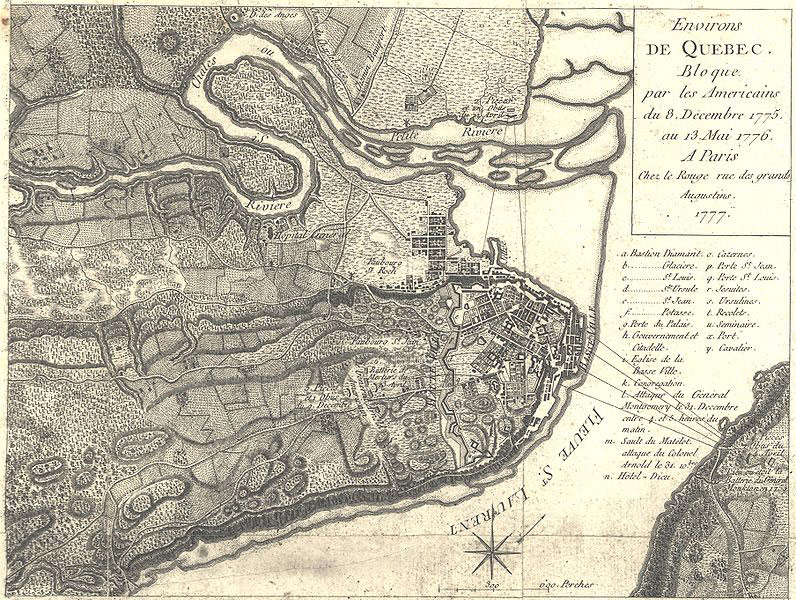

Montgomery arrived on December 1st and the force had deployed around Montreal to lay siege by the 6th. All messages delivered were burnt upon reception, Quebec retained faith in its walls. The artillery set up by the American forces had no real effect on the walls, so Arnold awaited a snowstorm which would enable his men to scale the fortress walls under cover. On the 27th such a storm arrived but soon faded, leaving Arnold with no choice but to concoct a different plan of attack. The matter was further compounded by the desertion of a Rhode Island sergeant who gave the plan of the original attack to the British.

A new plan was drafted which involved two diversionary attacks against Cape Diamond Bastion and St. Johns Gate in the North, these were to be conducted by two militia companies who would simply open fire at the targets but not attempt to storm them.

A new plan was drafted which involved two diversionary attacks against Cape Diamond Bastion and St. Johns Gate in the North, these were to be conducted by two militia companies who would simply open fire at the targets but not attempt to storm them.

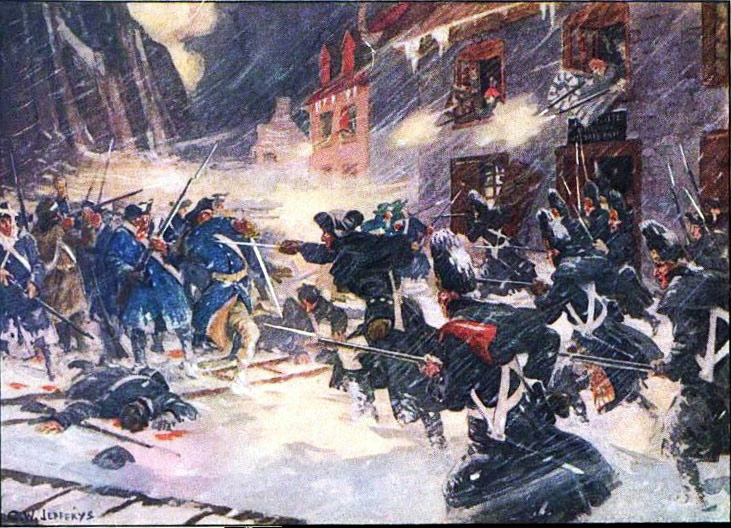

On the 30th of December another storm began and the order was given to attack. Montgomery, who had once been an officer in the British army, attacked the city in tandem with Arnold following the two feint attacks. The British general Carleton had set up a formidable deployment in addition to the already strong city walls and the American forces found themselves under heavy fire from the outset. Unbeknownst to them, recent enlistments had bolstered the defending forces numbers to 1,200. This was in part helped by the fact the British had threatened the French speaking populace to “volunteer” or face accusations of being spies or traitors. Ironically the feint attacks were too hasty and alerted the garrison to the imminent attacks.

Montgomery’s attack in the South was a complete failure and he was killed on the first day of the battle after storming a two-story building and taking shots to the head. He was killed instantly. He had led his forces through the outer palisades with the help of carpenters. The assault forces in the South lost so many of their officers and suffered such resistance that they retreated in disarray, leaving any chance of victory in tatters. Arnold’s assault in the East was more successful and the garrisons of the Sault-au-Matelot barricade were initially slow to respond. The British commander Carleton however had realized the Northern feints were of no threat and had already reinforced the lower town near the river including the northern section of the lower town where Arnold was attacking. Arnold, unaware of Montgomery’s death and the failure of the Southern push, was shot in the ankle after his force received heavy fire from the high stone walls and was carried off the field. Things were rapidly deteriorating for the American forces.

With Arnold injured, Daniel Morgan took command of the attack and ordered the men to take shelter within buildings near the palace gate in order to dry out their powder and rearm. It is well worth remembering that the average ammunition count for Arnold’s men stood at only five cartridges after the march from Boston and the aforementioned shortages.

With Arnold injured, Daniel Morgan took command of the attack and ordered the men to take shelter within buildings near the palace gate in order to dry out their powder and rearm. It is well worth remembering that the average ammunition count for Arnold’s men stood at only five cartridges after the march from Boston and the aforementioned shortages.

While Morgan attempted to rearm, 500 troops rushed forth from the gate and recaptured the palisade, trapping Morgan and all the men inside. Surrounded and under heavy fire, the entire contingent surrendered, marking the end of the battle at 10 a.m.

The Aftermath

Arnold refused to give up the siege and lay outside the city for nearly three months before being replaced. By May, the American commander, now General Thomas, concluded victory was impossible and ordered a retreat. The vanguard of a far larger British force, consisting of some 200 men, arrived on the 6th of May which spurred Carleton to sally forth from the city in order to conduct a joint attack on the now disorganized American troops.

The American forces retreated ravaged by smallpox and harried by British forces until they reached Ticonderoga Fort. General Thomas was lost on the journey from smallpox and the American Congress never again attempted to bring the Canadian populace into the revolution with them.