The Battle of Monmouth, also known as the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse, was an important battle in the American Revolution. The battle, fought on June 28, 1778 in New Jersey, featured British forces under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton and Continental forces under the command of General George Washington. While the battle resulted in a draw between the two sides, the fact that the Continental Army held their own against the more experienced British troops proved that the colonial forces were becoming more effective in their tactics and discipline.

The Battle of Monmouth, also known as the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse, was an important battle in the American Revolution. The battle, fought on June 28, 1778 in New Jersey, featured British forces under the command of Lieutenant General Sir Henry Clinton and Continental forces under the command of General George Washington. While the battle resulted in a draw between the two sides, the fact that the Continental Army held their own against the more experienced British troops proved that the colonial forces were becoming more effective in their tactics and discipline.

Prelude to Battle

In 1777, British forces captured the city of Philadelphia. However, when France entered the war as an ally of the Americans, Clinton, the British commander-in-chief of North American troops, evacuated Philadelphia under orders to consolidate his troops at the main British base in New York. When France entered the war, Clinton needed to send troops to West Florida and the West Indies to prevent French incursion into these outlying territories. As a result of this, Clinton could not continue to occupy Philadelphia and secure New York. In fact, he was under orders to abandon New York and withdraw to Quebec if the French reinforcements made the situation too uncertain.

While Clinton was shuffling his troops, a French fleet under the command of d’Estaing was on the way to meet American forces. If the French fleet made contact while Clinton’s troops were still moving to New York, the combined might of the American and French troops could prevent him from reaching the safety of the New York base. Originally Clinton planned to move his troops by sea with a Royal Navy escort. However, due to insufficient troop carriers, he was unable to do so. Instead, supplies and heavy equipment moved by sea along with fleeing American Loyalist civilians while the main army marched overland through New Jersey.

The march began on June 18, 1778 as the British forces began the 100 mile trek from Philadelphia to New York. With a total force numbering over 12,000 members and a baggage train stretching 12 miles long, the British advance faced a difficult journey made more challenging by obstacles created by opposing American forces. In addition to overwhelming heat and the normal difficulties of such a journey, the Americans added to the challenges by muddying wells, destroying bridges and blockading roads.

The march began on June 18, 1778 as the British forces began the 100 mile trek from Philadelphia to New York. With a total force numbering over 12,000 members and a baggage train stretching 12 miles long, the British advance faced a difficult journey made more challenging by obstacles created by opposing American forces. In addition to overwhelming heat and the normal difficulties of such a journey, the Americans added to the challenges by muddying wells, destroying bridges and blockading roads.

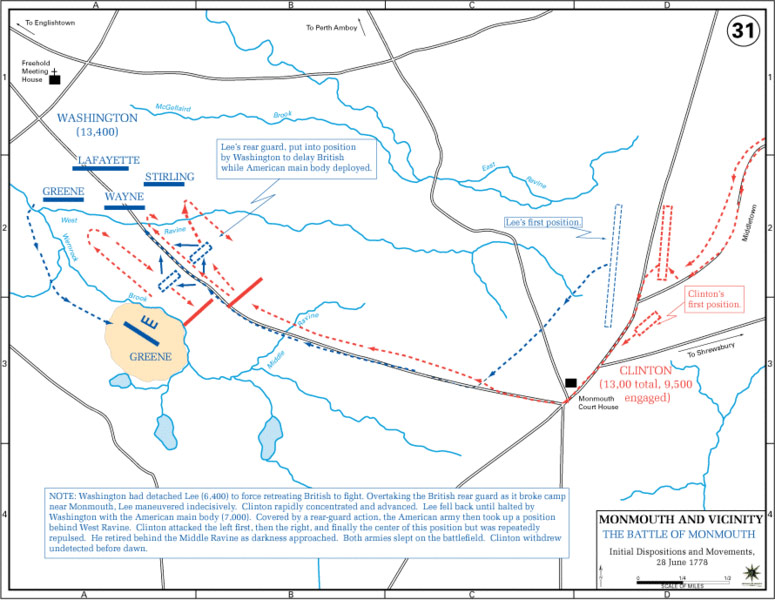

With both sides facing serious losses from heat stroke, Washington’s second in command, Major General Charles Lee, advocated waiting rather than committing forces in a battle against the British forces. However, Washington overruled him and moved American forces out from Valley Forge in pursuit. After consulting with his commanders, Washington laid plans to send an advanced force to attack the rear guard of the British as they left Monmouth Courthouse.

June 28, 1778

On the morning of June 28, the American forces launched their attack against the British rear guard. The unorganized attack, under Lee’s command, did not succeed, resulting first in a tactical retreat by several brigades and, later, a general retreat. When the British counterattacked, the retreat turned into a rout.

As Lee’s troops fled back down Monmouth road, they met the main body of the American forces advancing under Washington’s command. Washington relieved Lee of command, rallied the fleeing troops and redeployed them to delay the British forces while the main forces established positions. Once the main American forces were in position, Lee’s remaining troops joined them in their positions.

The British launched an attack against Washington’s troops, focusing on the left wing under the command of Major General Stirling. The battle continued on this front until additional American troops circled around and engaged the right flank of the attacking British troops. With the entrance of the relief troops, the British forces were repelled and retreated.

Next, the British launched a full-blown attack on the right wing. Cornwallis led the attack himself against the division led by Greene. Under heavy fire, the attacking British troops attempted to scale the ravine slope without success. After suffering heavy losses, including several ranking officers, the British retreated back down the slope. While the attack on the right was taking place, the British also attacked the American forward position commanded by Wayne. On their fourth attempt, the British forces finally succeeded in pushing Wayne’s troops back to the main American line.

Following the three skirmishes, both sides continued to fire cannons at each other but the British withdrew to a strong position along the eastern side of the ravine. Before Washington could press the attack, the sun had set and ended the day’s fighting. The next morning, the American troops discovered the British had withdrawn during the night and resumed their march. Washington did not pursue and the British withdrawal to New York continued without further incident.

After the Battle

Following the Battle of Monmouth, the British forces completed their march to New York, arriving in Sandy Hook on June 30. From there, the troops moved into New York City by boat where they began reinforcing the city against potential attack. The French fleet barely missed the chance to trap Clinton’s army before transport. As a result, plans to attack New York were put on hold and the city continued to serve as a primary British base for several more years.

Overall, the British troops achieved a tactical victory in the Battle of Monmouth as they were able to successfully complete their retreat to New York and reinforce the city. However, from a strategic perspective, neither side achieved true victory. While the British completed their movement, the Americans retained the field of battle and, for the first time, demonstrated their ability to hold their own against British soldiers. Several months later, Lee was court-martialed for his failure to provide adequate leadership and lost his command privileges for a period of one year. However, he ended up never serving in a military command position again.

As the last major battle of the northern theater, the Battle of Monmouth proved the benefits of the Continental Army’s encampment at Valley Forge. The continual training and drilling during the encampment significantly improved morale and discipline, allowing Washington to lead an effective force against British regulars and prove their ability to hold the field against an enemy. Despite the battle ending in a draw, the deeper consequences proved out over time as the Continental Army continued to leverage their developing war skills.