The Battle of Germantown in Philadelphia was yet another in a string of defeats for the American General George Washington in the Revolutionary War, but like so many of Washington’s setbacks, he had an uncanny ability to come away from a stinging military loss with an overall gain or advantage.

The Battle of Germantown in Philadelphia was yet another in a string of defeats for the American General George Washington in the Revolutionary War, but like so many of Washington’s setbacks, he had an uncanny ability to come away from a stinging military loss with an overall gain or advantage.

The Battle of Germantown took place on October 4, 1777 as the American Revolution entered its second year. There had been little to celebrate in terms of military success up until that point, although Washington had scored some minor successes, one of the most notable of which was his surprise victory in New Jersey at the Battle of Trenton.

But events were not to go so well on the ground for the rag-tag American army of patriots in Germantown, Pennsylvania, which was actually an outlying hamlet near the city of Philadelphia. The defeat at Germantown actually meant that the British would retain control of America’s capital city, which was Philadelphia at the time – it would be the first and last time a foreign power would ever conquer and control the Capital of the United States.

What is even more agonizing about the Battle of Germantown is that an American victory would certainly have ended the war and sent the British packing, but it was not meant to be. Part of the reason for the defeat was Washington’s overestimation of the capabilities of his inexperienced, poorly-trained army to carry out a fairly complicated battle plan. There was also some bad luck – dense fog in the area the morning of the battle created confusion and thwarted the ability of American forces to communicate and coordinate.

Prelude to the Battle of Germantown

At Germantown Washington once again faced his old nemesis, General William Howe, who had dealt the Americans a series of defeats throughout the previous year. About a month previous to Germantown, Howe had defeated Washington in the Battle of Brandywine on September 11 and also the Battle of Paoli on September 20. Howe then outmaneuvered Washington, enabling Howe and fellow British General Charles Cornwallis to seize Philadelphia.

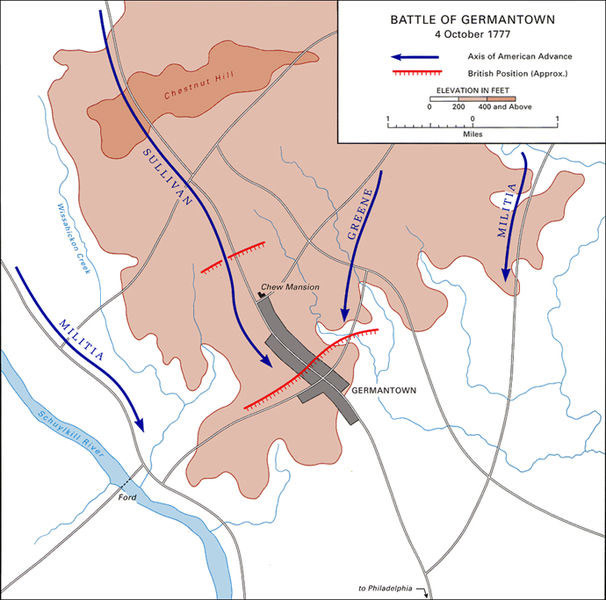

After the British took Philadelphia, Howe divided his forces, leaving more than 3,400 troops to occupy and hold the city, while mustering some 8,000 troops to Germantown. From this location Howe hoped to find, flush out, and engage Washington’s forces in the area.

October 4, 1777

Washington, however, considered this an opportunity. He reasoned that with Howe’s forces divided, it was a chance to attack the British troops in Germantown directly, and hopefully deal a significant blow to the British campaign. Washington wanted to attack at night to surprise his enemy the same way he did at Trenton.

Washington, however, considered this an opportunity. He reasoned that with Howe’s forces divided, it was a chance to attack the British troops in Germantown directly, and hopefully deal a significant blow to the British campaign. Washington wanted to attack at night to surprise his enemy the same way he did at Trenton.

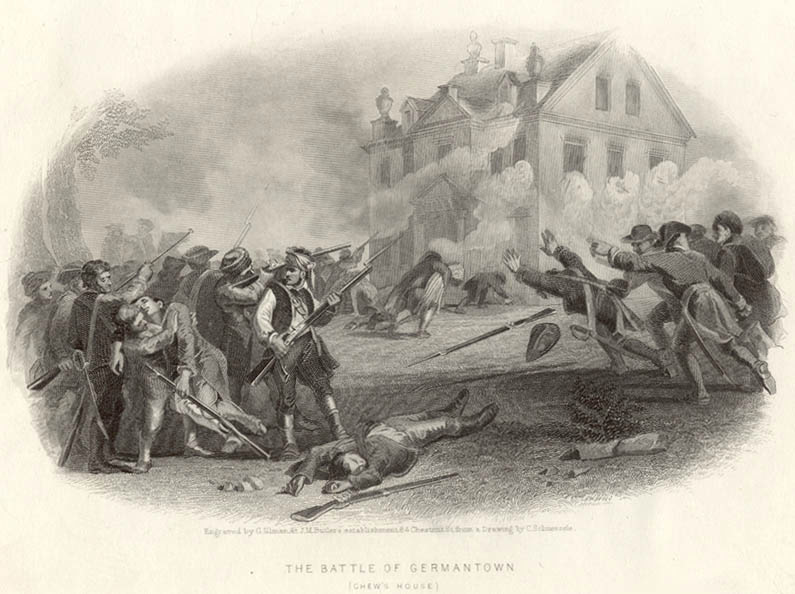

Although the attack did begin before dawn on the morning of October 4, the Americans were not able to make as much progress as they hoped. The darkness, and later a heavy morning fog, made communication difficult between the four columns sent against British positions. Although the Americans started successfully by routing a column of light British infantry, the greater British contingent was able to quickly rally and eliminate the element of surprise on which Washington had pinned much hope. Also, Washington rather rashly ordered further assaults on a number of key British positions, all of which were beaten back, spelling certain disaster for the American initiative.

Casualties

Despite having superiority in numbers with 11,000 troops to the 8,000 British, the Americans took more casualties. The official tally of the Battle of Germantown is 152 Americans killed, 521 wounded and 438 captured. By contrast, the British lost 71 men, 442 were wounded and 14 were listed as missing.

One of the most significant American casualties was General Francis Nash who had his leg blown off by a cannonball while leading his brigade in retreat. He survived the day, by died three days later. The British also lost a top-tier officer at Germantown, the Brigadier General James Agnew. He was shot by a civilian sniper by the name of Hans Boyer.

Significance of the Battle

So why is the Battle of Germantown considered one of the highlights for the Americans in the Revolutionary War? Well, as most seasoned military historians will tell you, most wars are not won on the battlefield, but in the halls of diplomacy, and what goes on behind the scenes. In the case of the Battle of Germantown, a number of powerful members of the French government were sufficiently impressed by the American effort at Germantown to move forward with significant political and military backing for the Revolutionaries. In short, the Americans might have been defeated in this bout, but powerful foreign observers were impressed enough by what they had seen to decide that the Americans could eventually win out in the long run.

One of those impressed by the performance of American forces at Germantown was Comte de Vergennes, a high-level French diplomat who had enormous influence within the French government. Another European power that was watching closely and liked what they saw at Germantown were representatives of Prussia, then led by Frederick the Great, one of the greatest military minds of his day.

European observers were incredibly impressed by the tenacity of Washington and the uncanny resolve of his army, all of whom had suffered defeat after defeat, including a thorough whipping just a month earlier at Brandywine and Paoli – yet they pressed the attack at Germantown. Indeed, if it had not been for the bad luck of the heavy morning fog, the American’s could easily have emerged victorious and ended the war.

Prussia and France, but mostly France, decided to weigh in heavily on the side of the newly formed United States of America. Once the French began to provide naval power to thwart the movement of British ships along the coasts, the Brits lost a significant element of their advantage in the overall war effort. French military advisors on the ground also proved invaluable in bringing higher professional standards to field commands.

It must also be noted that the British, inexplicably, failed to press their advantage after winning the Battle of Germantown. Like in so many other conflicts, they were content to win and withdraw, while allowing the Americans to withdraw as well and regroup to fight yet again. This persistent behavior on behalf of the British is one of the major reasons why they eventually lost the war of the American Revolution.