| Agustin de Iturbide | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Mexican Emperor | |

| In Power | 1822-1823 |

| Born | Sept. 27th, 1783 Valladolid |

| Died | July 19th, 1824 Padilla |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Caste | Criollo |

Agustin de Iturbide (1783-1824) was a Mexican politician and general. He is best known for his actions during the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, when the coalition he put together brought him control of the capital, Mexico City. Iturbide was named first as President and then as Emperor of the newly independent country. He is also said to have been involved in the design of the original flag of Mexico. He was eventually executed as a traitor.

Upbringing and Early Life

Iturbide was born on September 27, 1783, in what is now the city of Morelia, though at the time it was known as Valladolid. His family was of Basque origin, and were both aristocratic and rich. They were also devout Roman Catholics, and so Iturbide was sent to the town’s seminary to be educated. While he was not studying, he spent most of his time assisting with the management of an estate that was owned by his father. He married the daughter of the provincial governor, or intendant, Ana María Huarte, in 1805.

Having been granted a commission in the royal militia, Iturbide was soon becoming known for his exploits. He was promoted on several occasions during the struggle against liberals who were hoping to carry out a revolution. His daring feats led to his being both praised for his courage and his unorthodox strategy and criticized for his harsh treatment of those who opposed him. Iturbide was, by 1813, a colonel in charge of the Celaya regiment. He was also the military commandant of the governor of Guanajuato. In 1815, he was given the extra responsibility of being put in command of the Army of the North. The jurisdiction of this army covered both Guanajuato and Valladolid.

Thoughts of Independence

As part of a prominent group of young, aristocratic Mexican Creoles, Iturbide slowly came around to the idea that Mexico should split from its Spanish colonial power. This feeling was intensified in 1820, when an army rebellion in Spain resulted in a liberal regime coming to power. At the time, Iturbide was engaged, as commander of royal troops, in the pursuit of Vicente Guerrero, a high-profile liberal commander. The two men met and discussed terms, after which Guerrero promised that he would support the man who had so recently been his enemy.

Iturbide then began his own rebellion. On February 24, 1821, he published what was known as the Triguarantine Plan or the Plan of Iguala. This consisted of 23 articles, which set out a program of conservative policies. These would rest on three foundations: union, independence, and religion. The implication of the plan was that Iturbide would employ a larger number of Creoles, rather than Spaniards, in government jobs, but otherwise leave the colonial administration of Mexico largely untouched. Iturbe’s hope was that Mexico would become a Bourbon-led monarchy independent of Spain, with the promise of continued privileges based on Church and class.

The Treaty of Cordova

Iturbide’s proposals found immediate support from the majority of the Creole population. When Captain General Juan O’Donojú arrived later in 1821 to take up his role as viceroy, he discovered that Mexico was effectively being governed by Iturbide himself. After realizing that he did not have sufficient strength to challenge Iturbide militarily, O’Donojú asked for negotiations, which were granted, and resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Cordova.

Iturbide’s proposals found immediate support from the majority of the Creole population. When Captain General Juan O’Donojú arrived later in 1821 to take up his role as viceroy, he discovered that Mexico was effectively being governed by Iturbide himself. After realizing that he did not have sufficient strength to challenge Iturbide militarily, O’Donojú asked for negotiations, which were granted, and resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Cordova.

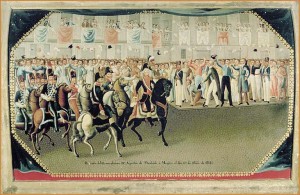

This agreement restated that Mexico was now to be considered an independent nation, which was to be headed by a prince of the Bourbon dynasty. Until the identity of a new monarch could be decided upon, the treaty continued, Iturbide would be appointed to lead a governing junta, which was to include O’Donojú among its members. By now Iturbide had come to revel in his nickname of Liberator, and on his 38th birthday, September 27, 1821, he led his army into Mexico city in triumph.

Reaching the Throne of Mexico

The title of ruler of newly independent Mexico was offered to several princes of Spain, but all of them rejected the terms. This helped to move sentiment among Mexican Creoles toward allowing Iturbide himself to receive the title. In May of 1822, a sergeant from Iturbide’s own Celaya regiment began pushing to have him proclaimed Mexican emperor. The man himself had to be persuaded to accept the honor, but Congress did make its formal choice the following day. The hall was packed with crowds of his followers, and initial doubts about the validity of the resolution were swept aside.

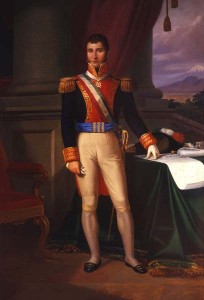

On July 22, amid much pomp and circumstance, Iturbide officially became Emperor Agustín I. His height and military bearing gave him a considerable presence well suited to his new imperial position. He followed this by trying to fashion his court after the magnificent European equivalents of the early 19th century, attempting also to retain the traditional Spanish rights of appointment of civil administrators and officials of the Church. By December, he was also active in trying to expand Mexican territory, although the army he sent to Central America did not succeed.

Fall and Execution

Iturbide was an undiplomatic ruler who failed to cultivate the relationships he needed to make his reign a success. He endured frequent arguments with an increasingly assertive legislature, which complained that he was taking too much power for himself. In the fall of 1822, he threw a number of deputies in jail and peremptorily ordered Congress dissolved. Iturbide had misjudged his position, and this was the final straw. Before long, a full-scale revolt had broken out.

The Emperor was forced to abdicate in March of 1823, after which he set sail for Europe. Hearing reports of a potential attack by Spain, he made an offer to “place his sword” at the disposal of his country, but this was seen by Congress as a ploy to regain control. Iturbide had already sailed for his homeland when Congress sentenced him to death for treason. He was immediately taken captive when he landed in Mexico, and died in front of a firing squad on July 19, 1824.